Ask Preeti Mistry why she cooks Indian food and you can almost hear the frustration in her voice.

"Well," she explains without hesitation, "it all goes back to chai."

Chai?

"This is a drink my family, and my grandparents, have been drinking every morning and every afternoon their entire lives," says the mohawked chef of Oakland's Juhu Beach Club and Navi Kitchen in Emeryville, California. And one day, mysteriously, the ur-beverage of South Asia began turning up at every coffee shop she encountered.

We weren't yet using terms like cultural appropriation, but "chai tea" marked something of a political awakening. Why, she wondered, are all these white people making money off it?

"You get made fun of in school for being weird, for being different, for having weird smells coming out of your house," says Mistry, who was born in London and raised in the United States. She kept the faith. "I knew I would get to the place where I can cook Indian food like the Indian food I love, and people will see there's more."

She was correct that there would be a new generation of diners - foodies - eager to dig their forks into the unfamiliar. There is also a new generation of chefs like Mistry: born or raised stateside, rewriting the script on what that cuisine should look and taste like.

Starting Thursday, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History hosts its annual Food History Weekend, which this year focuses on food's relationship with migration and cultural exchange. To mark the occasion, we spoke with several rising restaurateurs about how their experiences growing up in two cultures have affected their cooking and are redefining American food.

For the chefs, their love affair with food began, as it does for most, at home. One pinched dumplings alongside his mother; another learned to eat adventurously from his father. Their families turned to newspaper clippings and well-worn yard sale cookbooks to make their children lasagna and hamburgers on the nights they didn't serve japchae or roti.

Some of these chefs went to culinary school, some went to business school. And when they finally decided to open their own restaurants, the cuisine they chose to make surprised even them: It was the one they had grown up with.

"I don't think these folks set out to do this thing; it's just who they are," says former LA Weekly restaurant critic Besha Rodell, who began to notice the swell of young bicultural chefs a few years ago. "That's what makes it different from fusion. Fusion is taking one thing and banging it into another - like, wasabi in the mashed potatoes. This is authentic in the very real sense of the word, because it is their authentic, lived reality."

Now 41, Mistry is the one making money off her chai, which she serves at Navi Kitchen, with freshly roasted spices, sugar and milk, all boiled, the way it is in Mumbai. You can, if you must, get it with a shot of espresso.

- - -

Hannah and Marian Cheng

Mimi Cheng's, New York

The newest location of Mimi Cheng's dumpling shop is in Nolita, on the edge of New York's Chinatown, where dumpling shops seem to occupy every other storefront. This one is bright and cheery, with lush plants, pale walls and a print of a pineapple. It reflects the tastes of its proprietors, Hannah and Marian Cheng, 31 and 29, respectively. So does the menu, which is dotted with Taiwanese fare such as scallion pancakes and beef noodle soup, and also a macro bowl served with lemon-tahini dressing.

The sisters grew up in Upstate New York eating a mash-up of cuisines: Their father was raised in Taipei, where the cooking is light and not particularly spicy, while their mother was raised in Thailand. After Hannah graduated with a finance degree from Georgetown University, and Marian graduated from the University of Maryland having studied international business, they floated the idea of a restaurant. "Our parents," says Hannah, "were horrified and terrified."

"They were like, 'Why are you opening a Chinese takeout restaurant? We sent you to college.' "

They've adapted the fast casual model for their vision, with collaborations such as a truffle foie gras soup dumpling, crafted with Daniel Humm of Eleven Madison Park, and a vegan sweet potato-black bean-quinoa dumpling, with the trendy By Chloe.

Complaints about authenticity plague the sisters. "It's a running theme in the Yelp reviews," says Marian. "Organic chicken, or kale or zucchini, you're not going to find that in Taipei. But it's authentic to our family."

Others, sometimes other Chinese or Taiwanese Americans, complain about the price, which can be $12.50 for a bowl of chicken noodle soup. It's a subject that comes up repeatedly for second-generation restaurateurs.

The criticism is frequently an "Asian-on-Asian hate crime," Hannah jokes. But in all seriousness, she says, "We have a huge gripe with it. Ultimately, it's racism."

"We use the same meat distributors that the best restaurants in the city are using. We use the same vegetable distributors. So why would our meat be cheaper? Because we're Asian?"

- - -

Wesley Avila

Guerrilla Tacos, Los Angeles

Wesley Avila has a no-nonsense way about him. When Gary Menes of Le Comptoir asked him about his goals in a job interview, Avila told the chef he wanted to be a taquero - a taco slinger, the furthest thing from the tasting menu Menes would offer.

Menes wanted to serve his guests personally, from behind a counter. So did Avila. Menes gave him the job.

Avila had known taqueros all his life. He was raised in Pico Rivera, a largely Latino suburb in L.A. County. His mother was born just outside San Diego; his dad emigrated from Durango, Mexico, in the 1970s, washing cars at first, and then snagging a job at a cardboard factory that he held for more than 40 years. Listless for years after the tragic death of his mother when he was a teenager, Avila looked like he would put in a life at the same factory; he worked there as a forklift driver for seven years. His father finally intervened. "You guys are American," his father told him. "You should be able to go to school and have a career, and do something you want to do."

Avila ultimately quit his job and went to culinary school. He went to Mexico and France and Spain to educate himself and spent years in fine dining. Now 39, Avila launched Guerrilla Tacos in 2012. It took its name from the fact that Avila's taco cart was, at first, a rogue, unpermitted operation. Now a food truck, Guerrilla Tacos might sell a sweet potato taco with French feta and romesco-like salsa one day, or a wild boar taco another.

"I really identify as Angeleno - from L.A.," he said. "What my food represents isn't necessarily Mexican, and it isn't high-end. It's Angeleno; it's a melting pot."

- - -

Daniela Soto-Innes

Cosme and Atla, New York

Daniela Soto-Innes moved to Houston from Mexico City at age 12, with the blood of a family of cooks in her veins. A great-grandmother, Luz, had traveled to Paris to train as a cook, and her grandmother managed a bakery, she says while sipping a fresh cashew-milk cappuccino at Atla, the casual modern Mexican restaurant she helms with Enrique Olivera (of Pujol fame).

It was her mother, a lawyer, who enrolled Soto-Innes, 27, in a culinary training program outside Houston when she was just 13. One day, she recalls, a chef came to a class and told them, "You're not going to make any money for eight years. If you're good, maybe five." Perhaps thinking she ought to start early, Soto-Innes began pestering the chef, who worked for a Marriott, for a job. It was two years before the hotel relented.

After a stint at Underbelly in Houston, an apprenticeship at Pujol in Mexico City connected her to Olivera, who eventually tapped Soto-Innes to helm his U.S. spinoffs. She received the rising star chef award from the James Beard Foundation for 2016.

At Atla and Cosme, servers and bartenders must frequently lean in to explain dishes - memela, tlayuda - from Oaxaca and Puebla and Mexico City. She has more she wants to teach, from encouraging kindness in the restaurant industry to educating diners "that Mexican food can be contemporary." It is already working. One magazine's recent headline blared that Atla was a "restaurant designed for how New Yorkers eat now."

- - -

Preeti Mistry

Juhu Beach Club and Navi Kitchen, California

As one of three girls in her Ohio household, Preeti Mistry viewed cooking with suspicion. It was "just another household chore I didn't want any part of," she recalls. "But I liked to eat. I was always really curious."

It was only at age 19, when she moved with her now-wife, Ann Nadeau, to San Francisco's Mission neighborhood, that she began whipping up vegetarian dishes for their friends. At the urging of Ann and her friends, she enrolled at Le Cordon Bleu in London. She landed a job as a chef at Google, then was selected as a contestant on "Top Chef," where she was booted in the third episode of Season 6, but had made her name known.

Ann nudged her again, this time to follow through on her dream of opening a pop-up, Juhu Beach Club, in a dodgy liquor store near their place in San Francisco, before it moved to Oakland. The menu includes a fiery riff on Cracker Jack, duck salad in a tamarind dressing and pav, roughly described as Indian sliders. At Navi Kitchen, she serves pizza. What of it?

On the walls of Juhu Beach Club, which she will probably close this year, she took pains to hang photos of her family and friends not in exotic settings but as their lives really were, in London, in Trinidad and in the United States.

"I'm not trying to re-create something that exists in India," she says. "This is about the journey."

- - -

Danny Lee

ChiKo, Washington, D.C.

"As long as I could remember, our house was always the house that had people over for dinner," says Danny Lee. "For my sister and I, some of our best memories are sitting around the kitchen table, just folding dumplings."

Overseeing them was his mother, Yesoon Lee, who grew up in Seoul, South Korea. She immigrated to Illinois for graduate school in the early 1970s, before meeting her husband and moving to the Virginia suburbs. There, she became a social butterfly with a reputation as a formidable cook.

When Lee was 15, his father died, and to earn more money, Yesoon bought her way into a deli business, Picca-Deli, in Alexandria, Virginia, and then a pan-Asian eatery at the airport, hawking sesame beef. "My mom's generation, no one [in America] knew what Korean food was," Lee, 36, says. "Her generation, to make money, they couldn't cook Korean food."

But Lee was born here. "I can't speak Korean that well. I'm, like, the whitest Korean person I know," he jokes. "But I grew up eating Korean food. I was immersed in it."

In 2006, his family opened Mandu, the Korean word for the dumplings they once all made together as a family. His mom is its chef.

But at ChiKo on Capitol Hill, opened this summer, only the faintest impression of his Korean upbringing is evident. Lee is one of two chefs: The "Ko" in the name represents his Korean heritage, while the "Chi" represents fellow chef Scott Drewno's Chinese cooking prowess. Stainless steel bowls arrive at tables like a stream of consciousness, filled with charred Brussels sprouts or sweet, vinegary slabs of daikon dyed highlighter-yellow with turmeric. One of the most buzzy dishes is brisket, not exactly a staple of traditional Korean cooking. For Lee, the restaurant is a playground, where he can serve a meat more often layered between two slices of rye bread than over a bowl of rice with furikake butter.

A decade ago, this sort of fare might have been called fusion. But Lee and Drewno shrug at the idea of definitions.

"Cuisines evolve," Lee says. "People have their idea that bulgogi has to be a certain way and bibimbap has to be a certain way, and anything else is fusion. Or Americanized."

"We do whatever we want," Drewno adds. "It's not really something that keeps us up at night."

- - -

Pawan, Nakul and Arjun Mahendro

Badmaash, Los Angeles

Nakul and Arjun Mahendro, Toronto-born brothers of Indian descent, insist that their family's Los Angeles restaurant Badmaash is not that kind of Indian restaurant, though it serves samosas and butter chicken.

That kind of restaurant has a terrible rap. "Why has Indian food stayed the same for the past five or six decades?" Nakul says. Because, he says, most of the early immigrants pouring into the United States through the 1980s were skilled professionals who couldn't always get work in their fields. "They go out and take any job they can," he says. "A restaurant job. But they haven't dedicated their life to the craft."

Pawan Mahendro, their father, was trained in Mumbai in French and Sichuan cooking before he arrived in Canada in 1982 in search of better prospects. He mopped floors, made salads, cooked Indian food in apartments for parties. "I've been to so many jobs, and they say, 'Let me show you how to use parsley.' " He always humbly took the lesson, no matter how much he already knew.

In Toronto, the whole family worked in restaurants. Nakul was starting out as a busboy, and their mother and Arjun settled in on the business side. Pawan opened an Indian restaurant. Eventually, Nakul says, "I wanted to move to New York and work in some fancy restaurant like Jean-Georges."

Pawan, who had worked for others for so long, stopped him. Why, he said, would Nakul "help some other guy build his restaurant?"

Together they settled on a move to Los Angeles, where they opened Badmaash with the notion that Indian food has no singular flavor. They serve lamb burgers and chicken tikka poutine (a nod to their Canadian upbringing) in a space decorated with a Warholian mural of Gandhi rocking shades.

"I fought with Yelp to be listed as Indian and also New American," Nakul says. "New American kept getting taken off. I kept adding it."

To him, it's a sign that while some get what Badmaash is trying to do, there's work that remains. "This is the new America," he sighs. "It's the old America as well."

- - -

Arbol Salsa

14 servings (makes 1 3/4 cups)

This spicy green salsa has a fairly smooth, saucy consistency, which makes it great for spooning over Chubbs Tacos.

MAKE AHEAD: The salsa can be refrigerated in an airtight container for up to 1 week.

Adapted from "Guerrilla Tacos: Recipes From the Streets of L.A.," by Wesley Avila with Richard Parks III (Ten Speed Press, 2017).

Ingredients

2 to 3 tablespoons vegetable oil

1/2 ounce dried arbol chile peppers, stemmed (seeds removed for a slightly less spicy salsa)

1 teaspoon cumin seed

1 pound tomatillos, husked and rinsed

6 cloves garlic, each cut in half

3/4 cup water, or more as needed

Kosher salt

2 tablespoons distilled white vinegar, or more as needed

Steps

Heat 1 tablespoon of the oil in a medium-size cast-iron skillet over medium heat. Once the oil shimmers, add the chiles and cook for 2 to 3 minutes, stirring often, until toasted on all sides. (The chiles will be quite aromatic and the oil may sputter, so open a window or vent and be attentive.)

Add the cumin seed and toast for about 2 minutes, stirring, until fragrant, then add the tomatillos, garlic and 1 tablespoon of oil. If that amount of oil is not enough to coat all the tomatillos, add the remaining tablespoon. Cook until the tomatillos brown and blister slightly, using tongs to turn them over, about 2 minutes.

Add the water and cook, turning the tomatillos over occasionally. (It's useful to have a splatter screen here.) As the water evaporates, add more of it, 1/4 cup at a time, to prevent burning; we used 3/4 cup water in total. It should take 12 to 15 minutes for the tomatillos to become completely soft, with little water left in the pan.

Transfer the contents of the skillet to a blender; remove the center knob in the lid so steam can escape. Place a paper towel over that opening and puree on HIGH until fairly smooth. Season lightly with salt and add the 2 tablespoons of vinegar.

Let cool completely before tasting and adjusting the seasoning and/or vinegar, as needed.

Nutrition | Per 2 tablespoon-serving (using 1/2 teaspoon salt): 35 calories, 0 g protein, 3 g carbohydrates, 3 g fat, 0 g saturated fat, 0 mg cholesterol, 40 mg sodium, 0 g dietary fiber, 2 g sugar

- - -

Chubbs Tacos

4 servings

Guerrilla Tacos chef Wesley Avila is correct in saying that this street food is not quite like anything you can get anywhere else: Based on how his dad (whom he nicknamed "Chubbs") used to fry fluffy eggs in lard for tacos when Avila was a kid.

We tested the recipe with lard and also with the combination of clarified butter and vegetable shortening that is listed in the ingredients. We also garnished the tacos with fried chicken skins because we had the skins on hand; you can buy fried pork cracklings/skins at Latino markets.

Ghee, a type of clarified butter, is available in the international aisle of some large supermarkets.

Also adapted from "Guerrilla Tacos" (Ten Speed Press, 2017).

Ingredients

1/4 cup clarified butter or ghee (see NOTES)

1/4 cup vegetable shortening

4 large eggs

1 medium red or white onion, minced

1/2 teaspoon kosher salt

Handful of pork cracklings, chicharrones or fried chicken skins (see headnote and NOTES)

1 cup homemade or canned pinto beans, broth or can liquid reserved (see NOTES)

Four 6-inch corn tortillas, warmed

Arbol Salsa (see related recipe, at left) or your favorite green salsa, for serving

6 ounces queso fresco, sliced or crumbled, for serving

Flesh of 1/2 ripe avocado, sliced, for serving

4 dried arbol chile peppers, for serving

Chopped scallions, for serving

Steps

Combine the clarified butter (or ghee) and vegetable shortening in a medium skillet over medium-high heat. Line a plate with paper towels.

Crack the eggs into a bowl, then add the onion and kosher salt, whisking until well incorporated.

Once the butter-shortening mixture is shimmering (and measures about 340 degrees on an instant-read thermometer), pour one-quarter of the egg mixture into the skillet. Cook, undisturbed, for about 1 1/2 to 2 minutes; the egg's edges will crisp and crinkle, and the underside will brown like a pancake. Carefully flip the egg over, top with the cracklings, then use a spoon to baste the cracklings with some of the fat in the pan. Cook for about 30 seconds to 1 minute, then transfer the egg to the lined plate. Repeat with the egg mixture to make 3 more puffy fried eggs.

Discard all but 2 tablespoons of the butter/shortening from the pan (you may not need to discard any), then add the beans. Use the back of a wooden spoon to lightly mash about half the beans, and add 2 to 3 tablespoons of the reserved bean liquid (or water, if needed) until the beans are thinned to the consistency of hummus.

Divide the warm tortillas among individual plates. Spread 2 tablespoons of the beans onto each one, then top each portion with a puffy fried egg, a spoonful or two of the salsa, some cheese, avocado slices, a dried chile de arbol and scallions. Serve right away, with more salsa on the side.

NOTES: To cook your own pinto beans, rinse 1 cup dried pinto beans and put in a medium pot; cover with water by 2 inches, then bring to a boil over medium heat. Add 1 small yellow quartered onion, 1 bay leaf and 6 whole cloves of garlic, then lower the heat so the beans cook at a low boil. Cook, partially covered, for about 2 hours, until soft but not falling apart; you may need to add more water to the pot.

(The cooking time will be reduced if you use pre-soaked beans.) Stir in 1/2 teaspoon kosher salt. Let the beans cool in their broth, then discard the onion, bay leaf and garlic cloves. The yield is about 2 1/2 cups (with broth). Store any leftover beans in their broth for up to 1 week.

To clarify butter, melt unsalted butter over low heat, without stirring. Let it sit for several minutes, then skim off the foam. Leave the milky residue at the bottom and use only the clear (clarified) butter on top.

To make fried chicken skins, heat 1 inch of oil in a medium skillet over medium heat. Cut chicken skin into 2-inch pieces, stretching them as flat as you can. Carefully place one in the oil; if the oil bubbles around them, add half the remaining pieces of skin and fry for about 8 minutes, turning them until they are crisp and evenly golden brown. Drain on paper towels and season lightly with salt.

Ingredients are too variable for a meaningful analysis.

- - -

Desi Jacks

16 to 18 servings (makes about 25 cups, with clumps)

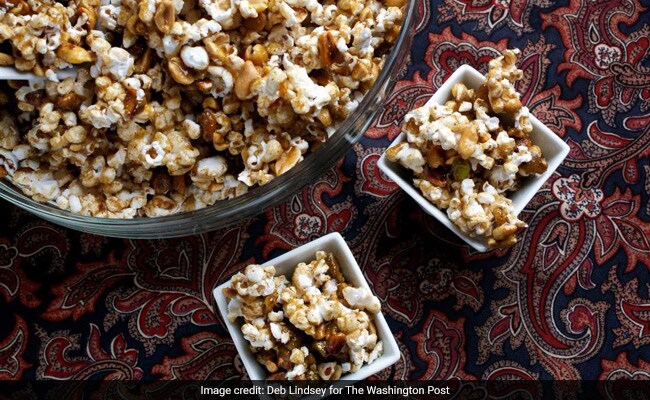

Rest assured that what seems like a huge amount of this sweet Indian-spiced snack will disappear quickly at any gathering. It was inspired by chef Preeti Mistry's love of Cracker Jack.

Using an air popper, as she suggests, reduces the risk of burnt popcorn bits. For the nuts, toast them in a pan on the stove top over low heat to prevent over-roasting that might occur once the Desi Jacks mix is in the oven. You'll need an instant-read or candy thermometer.

The recipe calls for Kashmiri chili powder, which is a bright, mild spice available at Indian markets. If you can't get it, do not substitute with the red chili powders in the grocery store. But you could use a ground cayenne pepper - and adjust the amount, accordingly, because it is more pungent. Ghee, a type of clarified butter, is available in the international aisle of some large supermarkets.

Adapted from "The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook: Indian Spice, Oakland Soul," by Preeti Mistry with Sarah Henry (Running Press, 2017).

Ingredients

1 tablespoon cumin seed

1 cup shelled, roasted unsalted pistachios (may substitute almonds or hazelnuts)

2 cups roasted unsalted peanuts

2 tablespoons neutral oil, such as canola or bran oil

1 tablespoon Kashmiri red chili powder (see headnote)

2 tablespoons kosher salt or coarse sea salt

16 cups popcorn, preferably popped using an air popper (see headnote; may substitute plain microwave-popped popcorn)

1/4 cup ghee or clarified butter (see headnote and NOTE; may substitute melted unsalted butter)

2 cups packed light brown sugar

1 cup light corn syrup

Steps

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Toast the cumin seed in a large, dry skillet over low heat for several minutes, until fragrant and lightly browned, shaking the pan occasionally to avoid scorching. Remove from heat and quickly grind to a fine powder.

In the same skillet, combine the pistachios, peanuts, oil, half the toasted ground cumin and half the chili powder, tossing to coat evenly. Season with 1 1/2 teaspoons of the salt. Toast on the stove top for 5 or 6 minutes over low heat, stirring frequently, until the nuts are a darker shade of brown. Let cool for 10 minutes or so.

Meanwhile, toss the popcorn with ghee, the remaining toasted ground cumin and chili powder. Taste and add 1 1/2 teaspoons of the salt. Transfer the mixture to a large, flat roasting pan.

Combine the brown sugar and corn syrup in a large, ovenproof saucepan over high heat. Bring to a boil and cook until it reaches 250 to 260 degrees; it will look like caramel. (This is a hardball stage for candy. Keep a bowl of water handy to test if you've arrived at the right consistency. Drop in a bit of the caramel; if it forms a ball you're able to pick up from the water, it's right.)

Fold in the nuts, then transfer the saucepan to the oven; bake (middle rack) for 5 minutes.

Carefully remove the saucepan from the oven, then pour the caramel over the popcorn in the roasting pan, tossing gently to coat and using a wide spatula to keep from squishing the popcorn. Sprinkle the remaining tablespoon of salt evenly over the mix, toss to incorporate. Let cool. Clumps will form; this is okay.

Finally, break apart any large clumps into bite-size pieces.

NOTE: To clarify butter, melt unsalted butter over low heat, without stirring. Let it sit for several minutes, then skim off the foam. Leave the milky residue at the bottom and use only the clear (clarified) butter on top.

Nutrition | Per serving (based on 18): 300 calories, 6 g protein, 47 g carbohydrates, 12 g fat, 2 g saturated fat, 0 mg cholesterol, 390 mg sodium, 3 g dietary fiber, 37 g sugar

(c) 2017, The Washington Post

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

"Well," she explains without hesitation, "it all goes back to chai."

Chai?

"This is a drink my family, and my grandparents, have been drinking every morning and every afternoon their entire lives," says the mohawked chef of Oakland's Juhu Beach Club and Navi Kitchen in Emeryville, California. And one day, mysteriously, the ur-beverage of South Asia began turning up at every coffee shop she encountered.

We weren't yet using terms like cultural appropriation, but "chai tea" marked something of a political awakening. Why, she wondered, are all these white people making money off it?

"You get made fun of in school for being weird, for being different, for having weird smells coming out of your house," says Mistry, who was born in London and raised in the United States. She kept the faith. "I knew I would get to the place where I can cook Indian food like the Indian food I love, and people will see there's more."

She was correct that there would be a new generation of diners - foodies - eager to dig their forks into the unfamiliar. There is also a new generation of chefs like Mistry: born or raised stateside, rewriting the script on what that cuisine should look and taste like.

Starting Thursday, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History hosts its annual Food History Weekend, which this year focuses on food's relationship with migration and cultural exchange. To mark the occasion, we spoke with several rising restaurateurs about how their experiences growing up in two cultures have affected their cooking and are redefining American food.

For the chefs, their love affair with food began, as it does for most, at home. One pinched dumplings alongside his mother; another learned to eat adventurously from his father. Their families turned to newspaper clippings and well-worn yard sale cookbooks to make their children lasagna and hamburgers on the nights they didn't serve japchae or roti.

Some of these chefs went to culinary school, some went to business school. And when they finally decided to open their own restaurants, the cuisine they chose to make surprised even them: It was the one they had grown up with.

"I don't think these folks set out to do this thing; it's just who they are," says former LA Weekly restaurant critic Besha Rodell, who began to notice the swell of young bicultural chefs a few years ago. "That's what makes it different from fusion. Fusion is taking one thing and banging it into another - like, wasabi in the mashed potatoes. This is authentic in the very real sense of the word, because it is their authentic, lived reality."

Now 41, Mistry is the one making money off her chai, which she serves at Navi Kitchen, with freshly roasted spices, sugar and milk, all boiled, the way it is in Mumbai. You can, if you must, get it with a shot of espresso.

- - -

Hannah and Marian Cheng

Mimi Cheng's, New York

The newest location of Mimi Cheng's dumpling shop is in Nolita, on the edge of New York's Chinatown, where dumpling shops seem to occupy every other storefront. This one is bright and cheery, with lush plants, pale walls and a print of a pineapple. It reflects the tastes of its proprietors, Hannah and Marian Cheng, 31 and 29, respectively. So does the menu, which is dotted with Taiwanese fare such as scallion pancakes and beef noodle soup, and also a macro bowl served with lemon-tahini dressing.

The sisters grew up in Upstate New York eating a mash-up of cuisines: Their father was raised in Taipei, where the cooking is light and not particularly spicy, while their mother was raised in Thailand. After Hannah graduated with a finance degree from Georgetown University, and Marian graduated from the University of Maryland having studied international business, they floated the idea of a restaurant. "Our parents," says Hannah, "were horrified and terrified."

"They were like, 'Why are you opening a Chinese takeout restaurant? We sent you to college.' "

They've adapted the fast casual model for their vision, with collaborations such as a truffle foie gras soup dumpling, crafted with Daniel Humm of Eleven Madison Park, and a vegan sweet potato-black bean-quinoa dumpling, with the trendy By Chloe.

Complaints about authenticity plague the sisters. "It's a running theme in the Yelp reviews," says Marian. "Organic chicken, or kale or zucchini, you're not going to find that in Taipei. But it's authentic to our family."

Others, sometimes other Chinese or Taiwanese Americans, complain about the price, which can be $12.50 for a bowl of chicken noodle soup. It's a subject that comes up repeatedly for second-generation restaurateurs.

The criticism is frequently an "Asian-on-Asian hate crime," Hannah jokes. But in all seriousness, she says, "We have a huge gripe with it. Ultimately, it's racism."

"We use the same meat distributors that the best restaurants in the city are using. We use the same vegetable distributors. So why would our meat be cheaper? Because we're Asian?"

- - -

Wesley Avila

Guerrilla Tacos, Los Angeles

Wesley Avila has a no-nonsense way about him. When Gary Menes of Le Comptoir asked him about his goals in a job interview, Avila told the chef he wanted to be a taquero - a taco slinger, the furthest thing from the tasting menu Menes would offer.

Menes wanted to serve his guests personally, from behind a counter. So did Avila. Menes gave him the job.

Avila had known taqueros all his life. He was raised in Pico Rivera, a largely Latino suburb in L.A. County. His mother was born just outside San Diego; his dad emigrated from Durango, Mexico, in the 1970s, washing cars at first, and then snagging a job at a cardboard factory that he held for more than 40 years. Listless for years after the tragic death of his mother when he was a teenager, Avila looked like he would put in a life at the same factory; he worked there as a forklift driver for seven years. His father finally intervened. "You guys are American," his father told him. "You should be able to go to school and have a career, and do something you want to do."

Avila ultimately quit his job and went to culinary school. He went to Mexico and France and Spain to educate himself and spent years in fine dining. Now 39, Avila launched Guerrilla Tacos in 2012. It took its name from the fact that Avila's taco cart was, at first, a rogue, unpermitted operation. Now a food truck, Guerrilla Tacos might sell a sweet potato taco with French feta and romesco-like salsa one day, or a wild boar taco another.

"I really identify as Angeleno - from L.A.," he said. "What my food represents isn't necessarily Mexican, and it isn't high-end. It's Angeleno; it's a melting pot."

- - -

Daniela Soto-Innes

Cosme and Atla, New York

Daniela Soto-Innes moved to Houston from Mexico City at age 12, with the blood of a family of cooks in her veins. A great-grandmother, Luz, had traveled to Paris to train as a cook, and her grandmother managed a bakery, she says while sipping a fresh cashew-milk cappuccino at Atla, the casual modern Mexican restaurant she helms with Enrique Olivera (of Pujol fame).

It was her mother, a lawyer, who enrolled Soto-Innes, 27, in a culinary training program outside Houston when she was just 13. One day, she recalls, a chef came to a class and told them, "You're not going to make any money for eight years. If you're good, maybe five." Perhaps thinking she ought to start early, Soto-Innes began pestering the chef, who worked for a Marriott, for a job. It was two years before the hotel relented.

After a stint at Underbelly in Houston, an apprenticeship at Pujol in Mexico City connected her to Olivera, who eventually tapped Soto-Innes to helm his U.S. spinoffs. She received the rising star chef award from the James Beard Foundation for 2016.

At Atla and Cosme, servers and bartenders must frequently lean in to explain dishes - memela, tlayuda - from Oaxaca and Puebla and Mexico City. She has more she wants to teach, from encouraging kindness in the restaurant industry to educating diners "that Mexican food can be contemporary." It is already working. One magazine's recent headline blared that Atla was a "restaurant designed for how New Yorkers eat now."

- - -

Preeti Mistry

Juhu Beach Club and Navi Kitchen, California

As one of three girls in her Ohio household, Preeti Mistry viewed cooking with suspicion. It was "just another household chore I didn't want any part of," she recalls. "But I liked to eat. I was always really curious."

It was only at age 19, when she moved with her now-wife, Ann Nadeau, to San Francisco's Mission neighborhood, that she began whipping up vegetarian dishes for their friends. At the urging of Ann and her friends, she enrolled at Le Cordon Bleu in London. She landed a job as a chef at Google, then was selected as a contestant on "Top Chef," where she was booted in the third episode of Season 6, but had made her name known.

Ann nudged her again, this time to follow through on her dream of opening a pop-up, Juhu Beach Club, in a dodgy liquor store near their place in San Francisco, before it moved to Oakland. The menu includes a fiery riff on Cracker Jack, duck salad in a tamarind dressing and pav, roughly described as Indian sliders. At Navi Kitchen, she serves pizza. What of it?

On the walls of Juhu Beach Club, which she will probably close this year, she took pains to hang photos of her family and friends not in exotic settings but as their lives really were, in London, in Trinidad and in the United States.

"I'm not trying to re-create something that exists in India," she says. "This is about the journey."

- - -

Danny Lee

ChiKo, Washington, D.C.

"As long as I could remember, our house was always the house that had people over for dinner," says Danny Lee. "For my sister and I, some of our best memories are sitting around the kitchen table, just folding dumplings."

Overseeing them was his mother, Yesoon Lee, who grew up in Seoul, South Korea. She immigrated to Illinois for graduate school in the early 1970s, before meeting her husband and moving to the Virginia suburbs. There, she became a social butterfly with a reputation as a formidable cook.

When Lee was 15, his father died, and to earn more money, Yesoon bought her way into a deli business, Picca-Deli, in Alexandria, Virginia, and then a pan-Asian eatery at the airport, hawking sesame beef. "My mom's generation, no one [in America] knew what Korean food was," Lee, 36, says. "Her generation, to make money, they couldn't cook Korean food."

But Lee was born here. "I can't speak Korean that well. I'm, like, the whitest Korean person I know," he jokes. "But I grew up eating Korean food. I was immersed in it."

In 2006, his family opened Mandu, the Korean word for the dumplings they once all made together as a family. His mom is its chef.

But at ChiKo on Capitol Hill, opened this summer, only the faintest impression of his Korean upbringing is evident. Lee is one of two chefs: The "Ko" in the name represents his Korean heritage, while the "Chi" represents fellow chef Scott Drewno's Chinese cooking prowess. Stainless steel bowls arrive at tables like a stream of consciousness, filled with charred Brussels sprouts or sweet, vinegary slabs of daikon dyed highlighter-yellow with turmeric. One of the most buzzy dishes is brisket, not exactly a staple of traditional Korean cooking. For Lee, the restaurant is a playground, where he can serve a meat more often layered between two slices of rye bread than over a bowl of rice with furikake butter.

A decade ago, this sort of fare might have been called fusion. But Lee and Drewno shrug at the idea of definitions.

"Cuisines evolve," Lee says. "People have their idea that bulgogi has to be a certain way and bibimbap has to be a certain way, and anything else is fusion. Or Americanized."

"We do whatever we want," Drewno adds. "It's not really something that keeps us up at night."

- - -

Pawan, Nakul and Arjun Mahendro

Badmaash, Los Angeles

Nakul and Arjun Mahendro, Toronto-born brothers of Indian descent, insist that their family's Los Angeles restaurant Badmaash is not that kind of Indian restaurant, though it serves samosas and butter chicken.

That kind of restaurant has a terrible rap. "Why has Indian food stayed the same for the past five or six decades?" Nakul says. Because, he says, most of the early immigrants pouring into the United States through the 1980s were skilled professionals who couldn't always get work in their fields. "They go out and take any job they can," he says. "A restaurant job. But they haven't dedicated their life to the craft."

Pawan Mahendro, their father, was trained in Mumbai in French and Sichuan cooking before he arrived in Canada in 1982 in search of better prospects. He mopped floors, made salads, cooked Indian food in apartments for parties. "I've been to so many jobs, and they say, 'Let me show you how to use parsley.' " He always humbly took the lesson, no matter how much he already knew.

In Toronto, the whole family worked in restaurants. Nakul was starting out as a busboy, and their mother and Arjun settled in on the business side. Pawan opened an Indian restaurant. Eventually, Nakul says, "I wanted to move to New York and work in some fancy restaurant like Jean-Georges."

Pawan, who had worked for others for so long, stopped him. Why, he said, would Nakul "help some other guy build his restaurant?"

Together they settled on a move to Los Angeles, where they opened Badmaash with the notion that Indian food has no singular flavor. They serve lamb burgers and chicken tikka poutine (a nod to their Canadian upbringing) in a space decorated with a Warholian mural of Gandhi rocking shades.

"I fought with Yelp to be listed as Indian and also New American," Nakul says. "New American kept getting taken off. I kept adding it."

To him, it's a sign that while some get what Badmaash is trying to do, there's work that remains. "This is the new America," he sighs. "It's the old America as well."

- - -

Arbol Salsa

14 servings (makes 1 3/4 cups)

This spicy green salsa has a fairly smooth, saucy consistency, which makes it great for spooning over Chubbs Tacos.

MAKE AHEAD: The salsa can be refrigerated in an airtight container for up to 1 week.

Adapted from "Guerrilla Tacos: Recipes From the Streets of L.A.," by Wesley Avila with Richard Parks III (Ten Speed Press, 2017).

Ingredients

2 to 3 tablespoons vegetable oil

1/2 ounce dried arbol chile peppers, stemmed (seeds removed for a slightly less spicy salsa)

1 teaspoon cumin seed

1 pound tomatillos, husked and rinsed

6 cloves garlic, each cut in half

3/4 cup water, or more as needed

Kosher salt

2 tablespoons distilled white vinegar, or more as needed

Steps

Heat 1 tablespoon of the oil in a medium-size cast-iron skillet over medium heat. Once the oil shimmers, add the chiles and cook for 2 to 3 minutes, stirring often, until toasted on all sides. (The chiles will be quite aromatic and the oil may sputter, so open a window or vent and be attentive.)

Add the cumin seed and toast for about 2 minutes, stirring, until fragrant, then add the tomatillos, garlic and 1 tablespoon of oil. If that amount of oil is not enough to coat all the tomatillos, add the remaining tablespoon. Cook until the tomatillos brown and blister slightly, using tongs to turn them over, about 2 minutes.

Add the water and cook, turning the tomatillos over occasionally. (It's useful to have a splatter screen here.) As the water evaporates, add more of it, 1/4 cup at a time, to prevent burning; we used 3/4 cup water in total. It should take 12 to 15 minutes for the tomatillos to become completely soft, with little water left in the pan.

Transfer the contents of the skillet to a blender; remove the center knob in the lid so steam can escape. Place a paper towel over that opening and puree on HIGH until fairly smooth. Season lightly with salt and add the 2 tablespoons of vinegar.

Let cool completely before tasting and adjusting the seasoning and/or vinegar, as needed.

Nutrition | Per 2 tablespoon-serving (using 1/2 teaspoon salt): 35 calories, 0 g protein, 3 g carbohydrates, 3 g fat, 0 g saturated fat, 0 mg cholesterol, 40 mg sodium, 0 g dietary fiber, 2 g sugar

- - -

Chubbs Tacos

4 servings

Guerrilla Tacos chef Wesley Avila is correct in saying that this street food is not quite like anything you can get anywhere else: Based on how his dad (whom he nicknamed "Chubbs") used to fry fluffy eggs in lard for tacos when Avila was a kid.

We tested the recipe with lard and also with the combination of clarified butter and vegetable shortening that is listed in the ingredients. We also garnished the tacos with fried chicken skins because we had the skins on hand; you can buy fried pork cracklings/skins at Latino markets.

Ghee, a type of clarified butter, is available in the international aisle of some large supermarkets.

Also adapted from "Guerrilla Tacos" (Ten Speed Press, 2017).

Ingredients

1/4 cup clarified butter or ghee (see NOTES)

1/4 cup vegetable shortening

4 large eggs

1 medium red or white onion, minced

1/2 teaspoon kosher salt

Handful of pork cracklings, chicharrones or fried chicken skins (see headnote and NOTES)

1 cup homemade or canned pinto beans, broth or can liquid reserved (see NOTES)

Four 6-inch corn tortillas, warmed

Arbol Salsa (see related recipe, at left) or your favorite green salsa, for serving

6 ounces queso fresco, sliced or crumbled, for serving

Flesh of 1/2 ripe avocado, sliced, for serving

4 dried arbol chile peppers, for serving

Chopped scallions, for serving

Steps

Combine the clarified butter (or ghee) and vegetable shortening in a medium skillet over medium-high heat. Line a plate with paper towels.

Crack the eggs into a bowl, then add the onion and kosher salt, whisking until well incorporated.

Once the butter-shortening mixture is shimmering (and measures about 340 degrees on an instant-read thermometer), pour one-quarter of the egg mixture into the skillet. Cook, undisturbed, for about 1 1/2 to 2 minutes; the egg's edges will crisp and crinkle, and the underside will brown like a pancake. Carefully flip the egg over, top with the cracklings, then use a spoon to baste the cracklings with some of the fat in the pan. Cook for about 30 seconds to 1 minute, then transfer the egg to the lined plate. Repeat with the egg mixture to make 3 more puffy fried eggs.

Discard all but 2 tablespoons of the butter/shortening from the pan (you may not need to discard any), then add the beans. Use the back of a wooden spoon to lightly mash about half the beans, and add 2 to 3 tablespoons of the reserved bean liquid (or water, if needed) until the beans are thinned to the consistency of hummus.

Divide the warm tortillas among individual plates. Spread 2 tablespoons of the beans onto each one, then top each portion with a puffy fried egg, a spoonful or two of the salsa, some cheese, avocado slices, a dried chile de arbol and scallions. Serve right away, with more salsa on the side.

NOTES: To cook your own pinto beans, rinse 1 cup dried pinto beans and put in a medium pot; cover with water by 2 inches, then bring to a boil over medium heat. Add 1 small yellow quartered onion, 1 bay leaf and 6 whole cloves of garlic, then lower the heat so the beans cook at a low boil. Cook, partially covered, for about 2 hours, until soft but not falling apart; you may need to add more water to the pot.

(The cooking time will be reduced if you use pre-soaked beans.) Stir in 1/2 teaspoon kosher salt. Let the beans cool in their broth, then discard the onion, bay leaf and garlic cloves. The yield is about 2 1/2 cups (with broth). Store any leftover beans in their broth for up to 1 week.

To clarify butter, melt unsalted butter over low heat, without stirring. Let it sit for several minutes, then skim off the foam. Leave the milky residue at the bottom and use only the clear (clarified) butter on top.

To make fried chicken skins, heat 1 inch of oil in a medium skillet over medium heat. Cut chicken skin into 2-inch pieces, stretching them as flat as you can. Carefully place one in the oil; if the oil bubbles around them, add half the remaining pieces of skin and fry for about 8 minutes, turning them until they are crisp and evenly golden brown. Drain on paper towels and season lightly with salt.

Ingredients are too variable for a meaningful analysis.

- - -

Desi Jacks

16 to 18 servings (makes about 25 cups, with clumps)

Rest assured that what seems like a huge amount of this sweet Indian-spiced snack will disappear quickly at any gathering. It was inspired by chef Preeti Mistry's love of Cracker Jack.

Using an air popper, as she suggests, reduces the risk of burnt popcorn bits. For the nuts, toast them in a pan on the stove top over low heat to prevent over-roasting that might occur once the Desi Jacks mix is in the oven. You'll need an instant-read or candy thermometer.

The recipe calls for Kashmiri chili powder, which is a bright, mild spice available at Indian markets. If you can't get it, do not substitute with the red chili powders in the grocery store. But you could use a ground cayenne pepper - and adjust the amount, accordingly, because it is more pungent. Ghee, a type of clarified butter, is available in the international aisle of some large supermarkets.

Adapted from "The Juhu Beach Club Cookbook: Indian Spice, Oakland Soul," by Preeti Mistry with Sarah Henry (Running Press, 2017).

Ingredients

1 tablespoon cumin seed

1 cup shelled, roasted unsalted pistachios (may substitute almonds or hazelnuts)

2 cups roasted unsalted peanuts

2 tablespoons neutral oil, such as canola or bran oil

1 tablespoon Kashmiri red chili powder (see headnote)

2 tablespoons kosher salt or coarse sea salt

16 cups popcorn, preferably popped using an air popper (see headnote; may substitute plain microwave-popped popcorn)

1/4 cup ghee or clarified butter (see headnote and NOTE; may substitute melted unsalted butter)

2 cups packed light brown sugar

1 cup light corn syrup

Steps

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees.

Toast the cumin seed in a large, dry skillet over low heat for several minutes, until fragrant and lightly browned, shaking the pan occasionally to avoid scorching. Remove from heat and quickly grind to a fine powder.

In the same skillet, combine the pistachios, peanuts, oil, half the toasted ground cumin and half the chili powder, tossing to coat evenly. Season with 1 1/2 teaspoons of the salt. Toast on the stove top for 5 or 6 minutes over low heat, stirring frequently, until the nuts are a darker shade of brown. Let cool for 10 minutes or so.

Meanwhile, toss the popcorn with ghee, the remaining toasted ground cumin and chili powder. Taste and add 1 1/2 teaspoons of the salt. Transfer the mixture to a large, flat roasting pan.

Combine the brown sugar and corn syrup in a large, ovenproof saucepan over high heat. Bring to a boil and cook until it reaches 250 to 260 degrees; it will look like caramel. (This is a hardball stage for candy. Keep a bowl of water handy to test if you've arrived at the right consistency. Drop in a bit of the caramel; if it forms a ball you're able to pick up from the water, it's right.)

Fold in the nuts, then transfer the saucepan to the oven; bake (middle rack) for 5 minutes.

Carefully remove the saucepan from the oven, then pour the caramel over the popcorn in the roasting pan, tossing gently to coat and using a wide spatula to keep from squishing the popcorn. Sprinkle the remaining tablespoon of salt evenly over the mix, toss to incorporate. Let cool. Clumps will form; this is okay.

Finally, break apart any large clumps into bite-size pieces.

NOTE: To clarify butter, melt unsalted butter over low heat, without stirring. Let it sit for several minutes, then skim off the foam. Leave the milky residue at the bottom and use only the clear (clarified) butter on top.

Nutrition | Per serving (based on 18): 300 calories, 6 g protein, 47 g carbohydrates, 12 g fat, 2 g saturated fat, 0 mg cholesterol, 390 mg sodium, 3 g dietary fiber, 37 g sugar

(c) 2017, The Washington Post

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world