Parasakthi is not merely a film set against history; it is history weaponised for the present. From its very first frame, the movie announces its political intent, rooting itself firmly in the anti-Hindi imposition agitations of the 1950s and 60s - a movement that did not just shake the streets of Tamil Nadu but fundamentally altered its political destiny by propelling the DMK to power.

There is nothing subtle about this film, nor is it meant to be. Parasakthi is an unapologetically political work that evokes fear, pride, anger, and resistance - emotions deeply embedded in Tamil society when it comes to language, identity, and cultural survival. The anxiety over Hindi imposition and the threat it poses to Tamil and other regional languages is not a relic of the past; it remains a powerful countercurrent to the BJP's Hindutva project even today. The film understands this-and exploits it masterfully.

Though set during the Nehru-Indira Gandhi era, with explicit references to the violent and uncompromising resistance to the Centre's language policies, Parasakthi clearly serves a contemporary political purpose. It explains, almost pedagogically, the origins of the DMK's historic opposition to the three-language formula and positions the party as the singular defender of Tamil identity against north Indian cultural dominance.

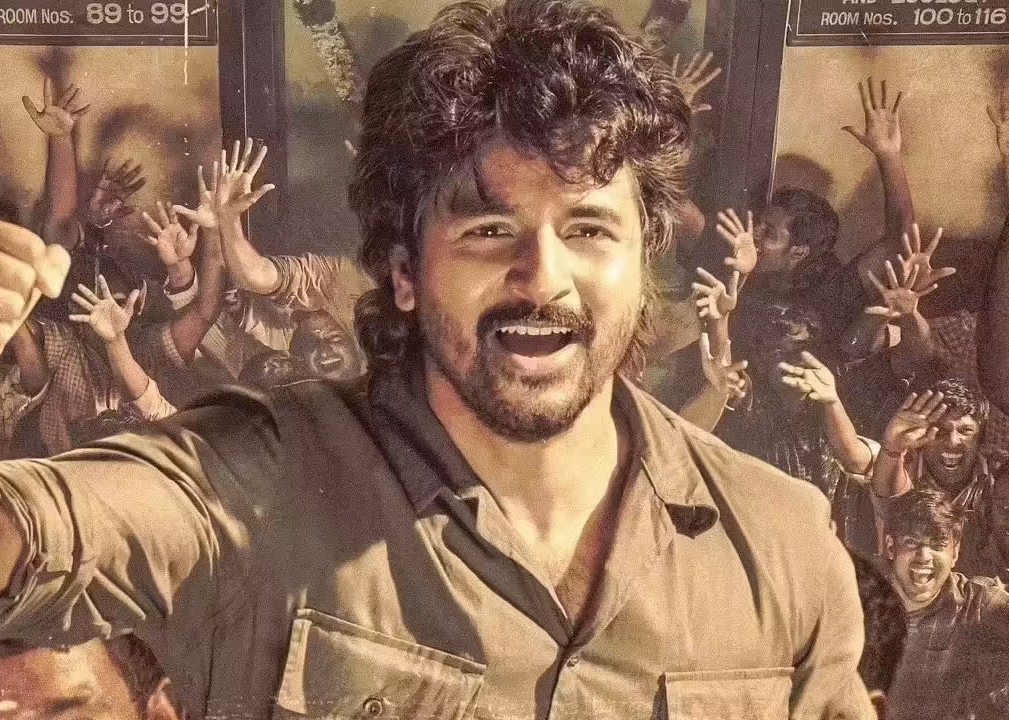

The film does not shy away from foregrounding DMK icons like CN Annadurai and M Karunanidhi as champions of the Tamil cause. Yet, its protagonist, Sezhian - played by Sivakarthikeyan - is not a biographical stand-in for any one leader. Instead, he is a symbolic construct: the distilled essence of the student and youth movements that formed the emotional backbone of the anti-Hindi agitations.

Even the name "Sezhian" is political. Rooted in Tamil and meaning "prosperity," it reflects the Dravidian ideological rejection of caste- and religion-marked names associated with Hindu deities. This tradition has deep roots in the Dravidian movement, exemplified by figures like the late Era Sezhian, who renounced his birth name R Sreenivasan in favour of a secular, Tamil identity. Names, in this political culture, are statements of resistance.

The title Parasakthi itself is a loaded choice. It immediately invokes the legendary 1952 film scripted by Karunanidhi, a cinematic manifesto of Dravidian rationalism and social revolution. There is little doubt that this naming is deliberate, designed to trigger memory, loyalty, and ideological nostalgia. It is political branding at its most effective.

That the film comes from Red Giant Movies only sharpens its political edge. The company's CEO, Inbanidhi, is the son of Deputy Chief Minister Udhayanidhi Stalin, whose name is conspicuously mentioned in the opening credits. To suggest that the film is anything other than political would be disingenuous. Parasakthi is cinema as political communication-crafted, timed, and positioned with precision.

Crucially, the film reinforces a central DMK argument often distorted by its opponents: the resistance is not to Hindi as a language, but to its imposition. One of the most striking moments sees the protagonist protesting in Delhi holding Tamil placards that read "Hindi Vazhga" (Long Live Hindi). The message is unmistakable - this is about federalism, dignity, and choice, not linguistic hatred.

The film also emphasises this with dialogues where the protagonist tells the central government minister (a reference to Indira Gandhi as I&B minister after Nehru's demise) that he is also firmly for the unity of the country, but what the centre is pushing for is uniformity and not unity.

In fact, the villain in the film is a fiercely patriotic police officer who wants to squash the Tamil agitation with brutal force. In a sense the narrative is a diehard nationalist facing off with the defender of Tamil!

By extending solidarity to Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, and Bengali voices, Parasakthi broadens the struggle beyond Tamil Nadu. It reframes Hindi imposition as a national issue of regional identity versus cultural centralisation, giving the film resonance far beyond state borders.

None of this would matter if the film failed as a cinema. It doesn't. Parasakthi is gripping, emotionally charged, and accessible across generations. Its narrative momentum ensures that ideology never feels like a lecture, but rather an experience.

Commercially, the film is poised for an unchallenged box-office run. Politically, it feeds directly into the DMK-versus-BJP language narrative at a strategically crucial moment. It may not single-handedly swing elections - cinema never does - but as a component of political mobilisation, it is immensely powerful.

So potent, in fact, that it may even give pause to non-DMK supporters, forcing a re-examination of what language, identity, and federalism truly mean in contemporary India.

Ultimately, Parasakthi strengthens the political standing of Udhayanidhi Stalin and his family, not merely as administrators, but as custodians of the Dravidian ideological legacy. This is cinema with intent, impact, and impeccable timing.

In Tamil Nadu, politics has more often than not found its loudest voice on the silver screen. Sudha Kongara, the director of a fantastic film, but more importantly a political masterpiece for the DMK in the electoral season. Parasakthi is an exaggerated, fiercely dramatized political version of history. But then facts don't matter while setting a political narrative in an election season.

(The author is Executive Editor, NDTV)

Disclaimer: These are the personal opinions of the author