Scientists at the University of Pennsylvania, in collaboration with the University of Michigan, have developed the world's smallest fully programmable and autonomous robots.

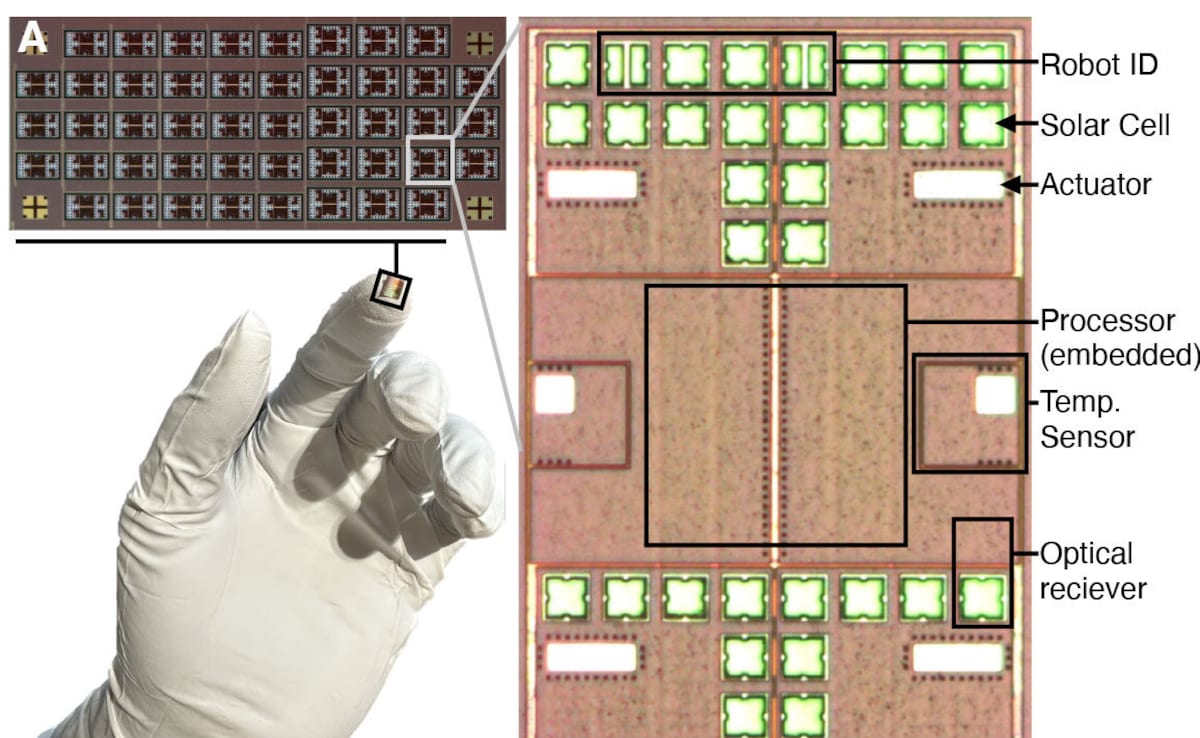

These micro-swimmers, about the size of microorganisms (0.2 x 0.3 x 0.05 millimetres), can move independently, sense their environment, and respond to changes, all while costing only a penny each.

Powered by light and guided by a micro "brain" developed at Michigan, the robots can perform tasks like sensing temperature and adjusting their movement patterns. Supported by the National Science Foundation, this innovation could significantly impact medicine by monitoring cell-level health and aid in building tiny, precise devices in manufacturing.

"We've made autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller," said Marc Miskin, assistant professor in electrical and systems engineering at Penn and senior author of a pair of studies published in Science Robotics and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots."

The robots can move in complex patterns and even travel in coordinated groups, much like a school of fish. And because their propulsion system has no moving parts, the robots are extremely durable-easy to transfer with a micropipette and capable of swimming for months.

Image credit: Maya Lassiter, University of Pennsylvania

For decades, electronics have gotten smaller and smaller, epitomized by the record-setting sub-millimeter computers developed in the lab of David Blaauw and Dennis Sylvester, professors of electrical and computer engineering at U-M. Yet robots have struggled to keep pace, in part because independent motion is exceptionally difficult for microscale devices-a problem Miskin says has stalled the field for 40 years, until now.

"We saw that Penn Engineering's propulsion system and our tiny computers were just made for each other," said Blaauw, a senior author of the Science Robotics study in a statement.

Operating at the microscale in water, drag and viscosity are so large that Miskin says it's like moving the robot through tar. His team's propulsion design gets around this by turning the problem around. Instead of trying to move themselves, these robots move the water. They generate an electrical field that nudges ions in the surrounding liquid. Those ions, in turn, push on nearby water molecules, generating force to move the robot. This mechanism is described in PNAS.

On the computing side, Blaauw's team needed to run the robot's program on 75 nanowatts of power, which he says is 100,000 times less than a smart watch requires. To get even that tiny amount of power, the solar panels take up most of the robot.

"We had to totally rethink the computer program instructions, condensing what conventionally would require many instructions for propulsion control into a single, special instruction to help us shrink the program's length to fit in the robot's tiny memory," Blaauw said.

The robots are both powered and programmed by light pulses, and each has their own unique identifier for individualized programming. This capability could enable a team of robots to each take a different part of a group task.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world