- In Madhya Pradesh, 20 children died after consuming a toxic cough syrup

- State Health Minister Rajendra Shukla declared twice, on October 1 and October 3, that the syrup was safe

- More than four weeks after the first deaths, Madhya Pradesh finally banned the syrup statewide

In Madhya Pradesh, 20 children are dead and seven more are battling for life after consuming a toxic cough syrup that should never have reached them.

What began as a series of mysterious deaths in Chhindwara has now turned into a chilling expose of how India's drug regulation system, meant to protect lives, collapsed under its own weight.

By September 29, 10 children had already died after consuming the cough syrup Coldrif, manufactured by a Tamil Nadu-based pharma company.

Yet, shockingly, the samples of the suspected medicine were dispatched to the state's drug testing lab not through an emergency channel or secured carrier but by ordinary registered post, the kind used to send letters, without tracking or urgency.

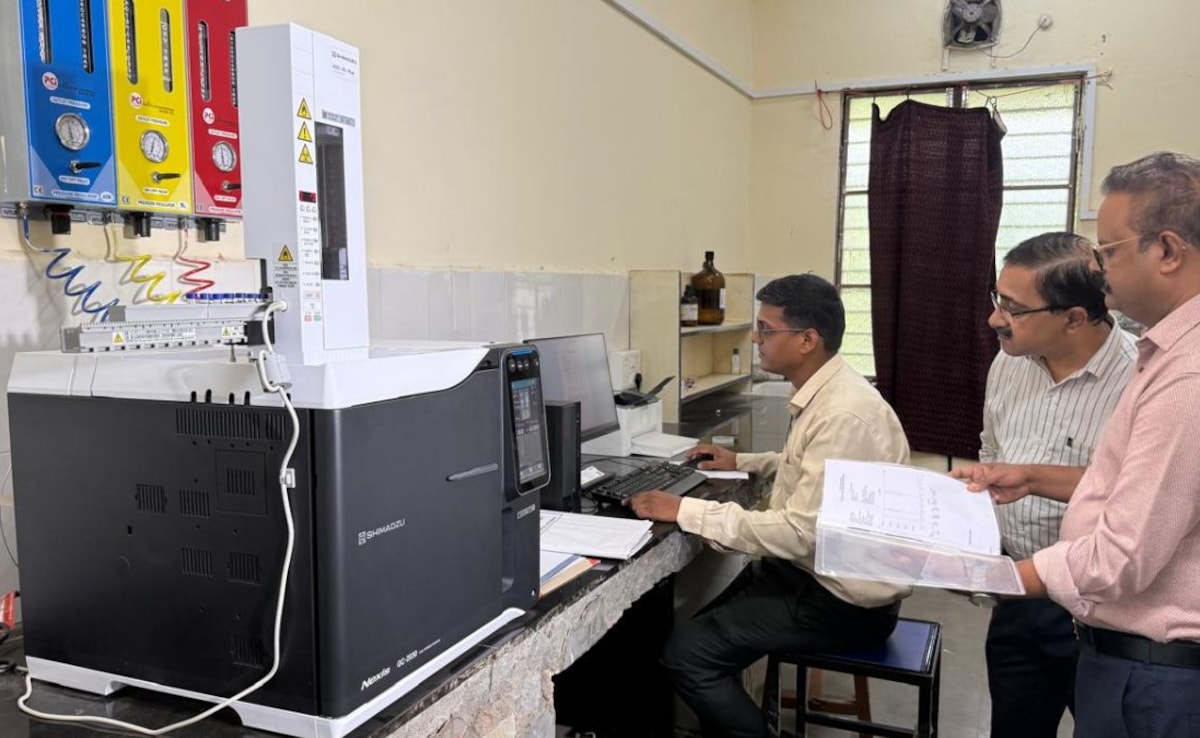

Drug testing lab in Bhopal

Even before the results arrived, Madhya Pradesh's Health Minister Rajendra Shukla declared twice, on October 1 and October 3, that the syrup was safe. He gave the drug a clean chit before any report was available, a decision that now stands in painful contrast to the bodies of children who had already died.

Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, acted with urgency. Its drug lab tested the same syrup and within forty-eight hours, confirmed it was toxic, immediately banning it.

But while Tamil Nadu was acting, Madhya Pradesh's own samples were still crawling through the postal system. It took three days to send them just from Chhindwara to Bhopal, a distance of barely three hundred kilometres. When lives depended on hours, the state lost days.

The first alerts about the deaths came on September 19, when reports from Nagpur indicated that a contaminated cough syrup might be involved. By September 22, a team from the state's health department had reached Chhindwara, followed by experts from the National Centre for Disease Control and the National Health Mission between September 26 and 28. Samples were collected, and local authorities temporarily banned the syrup's sale in Chhindwara on September 29.

But the ban was limited to the district, and the same medicine continued to be sold in nearby areas for days. On October 1, the Centre issued alerts about two suspect syrups, Nastro-DS and Coldrif. Two days later, Tamil Nadu's lab confirmed Coldrif to be substandard and dangerous.

It was only on October 4, more than four weeks after the first deaths, that Madhya Pradesh finally banned the syrup statewide. By then, the damage was irreversible.

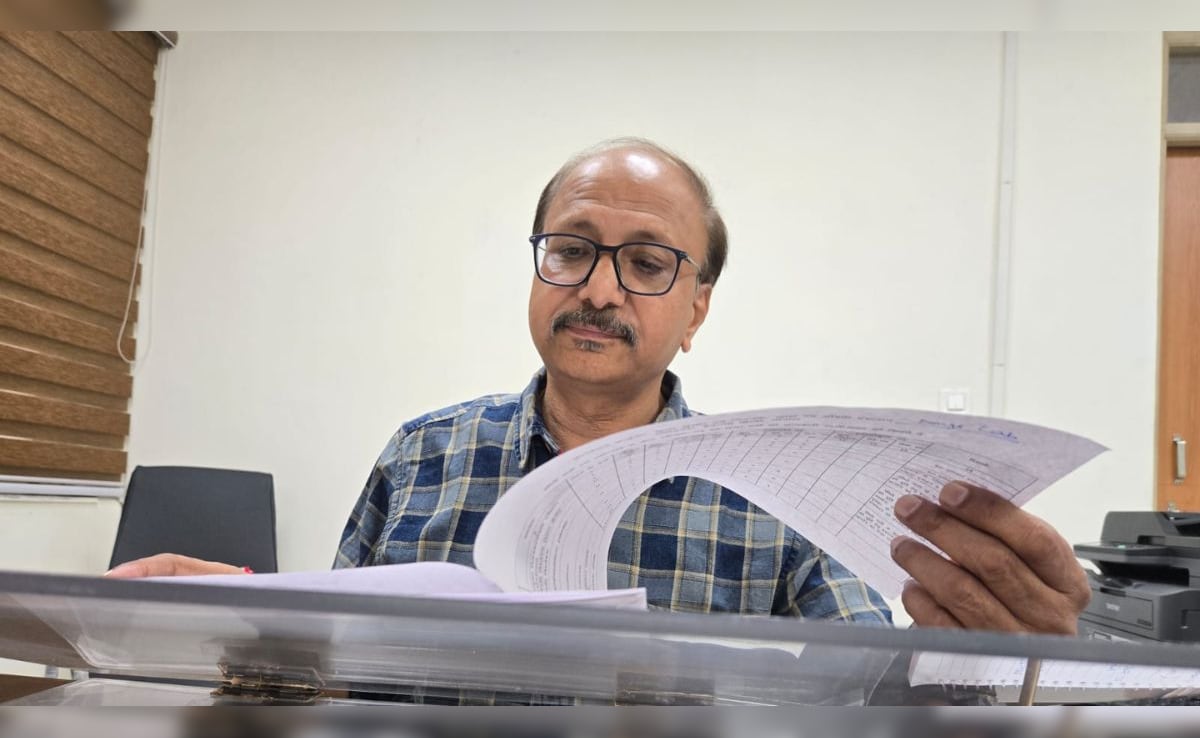

When NDTV questioned Madhya Pradesh's Drug Controller, Dinesh Srivastava, about why critical evidence in a case involving child deaths had been sent by registered post, he admitted it was routine practice.

Madhya Pradesh's Drug Controller, Dinesh Srivastava

"Traditionally, all samples are sent through registered post," he said, adding, "However, in emergencies, officers should seal and send them through special carriers. This matter is under investigation, and those responsible for delays have been suspended."

His response exposed a disturbing truth that even in times of crisis, the state's health machinery relies on outdated, mechanical processes better suited for routine paperwork than for saving lives.

Beyond procedural lapses, the tragedy has also uncovered the fragile infrastructure of Madhya Pradesh's drug testing system. The state operates just three drug laboratories in Bhopal, Indore and Jabalpur with a combined capacity to test only around six thousand samples a year.

Today, those labs are overflowing, with more than 5,500 samples pending for analysis. Each test takes two to three days, and the state has only 80 drug inspectors to oversee an entire population spread across 50 districts.

Officials quietly admit that at the current pace, it could take more than a year to clear the backlog. "Our three labs can test around 6,000 samples a year. It's clear we need to increase capacity, and we are reviewing that," Srivastava told NDTV. But for the families who have already lost their children, those assurances come too late.

The picture of neglect does not end there. Two mobile drug testing vans, bought at public expense to conduct on-the-spot quality checks, have been lying unused for years inside the compound of the Madhya Pradesh Food and Drug Administration in Bhopal's Idgah Hills. One of them hasn't moved since 2022; the other was never used at all.

Mobile drug testing lab

"Some rapid tests can be done in the van, but most chemical analyses require heavy equipment. It's under consideration," said Joint Controller Tina Yadav, when asked why they weren't deployed during the crisis.

The sight of these idle vehicles meant to prevent tragedies exactly like this has become an unmistakable symbol of bureaucratic paralysis.

As investigators now try to track every bottle of the killer syrup, disturbing figures are emerging. Of the 660 bottles of Coldrif distributed across Chhindwara and nearby districts, 457 have been seized, and 28 have been sent for testing. Another 156 were administered to patients, and 19 bottles remain missing. No one knows where they are or whether they have already reached homes and hospitals. Each untraced bottle represents a lingering danger, a reminder that this crisis may still not be over.

What the Chhindwara deaths have exposed is not just one company's negligence but a chain of systemic failures, a government that moved too slowly, labs that were overwhelmed, equipment that lay unused, and a regulatory framework that failed to recognise an emergency when it was staring right at it. From sending vital samples through regular post to declaring a drug safe without testing, every stage of the state's response has revealed a deeper malaise.

As the parents of 20 children mourn and seven children battle for their lives, Madhya Pradesh's health department continues to grapple with its own paperwork.

The warning signs were all there, ignored, delayed, and mishandled.

Even today, as toxic samples sit in government cupboards and testing vans gather dust, the system meant to safeguard the public remains dangerously unprepared for its next test.

The question now is no longer just who is responsible for this tragedy but whether Madhya Pradesh's drug control machinery can ever find its own cure.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world