In the global development landscape, certain indices such as the Human Development Index (HDI) and the Global Hunger Index, garner considerable attention in India. Yet, one of the most crucial monitoring systems for human well-being, the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP), remains relatively under-recognised.

Understanding JMP And Why It Matters

Established in 1990 and co-managed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNICEF, the JMP is the custodian of global data on water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). The JMP plays a central role in tracking progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDG 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

WASH is not only a matter of health and dignity; it is directly linked to education outcomes, economic productivity, gender equality, and environmental sustainability. Within the framework of HDI, access to safe drinking water and sanitation has a direct impact on life expectancy and the standard of living, making JMP findings a crucial lens for assessing human development worldwide.

Global Progress: Gains, But Short Of SDGs

The fifth Global JMP Report (2024), released in the last week of August 2025, offers both encouragement and caution. Globally, more people than ever before now have access to improved WASH services. Safe drinking water coverage has expanded, open defecation has reduced dramatically in several regions, and handwashing facilities have become more common.

Yet, the pace is insufficient. The report warns that when world population is 8 billion, millions of people cannot lack safely managed water and sanitation by 2030. At this pace of progress, indicated in the latest JMP 2024 report, we will have to wait until 2063 to reach the SDG 6.2 ambition of achieving access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all.

Rural-urban disparities remain glaring, and fragile states continue to lag far behind. Moreover, climate change is compounding risks, with droughts, floods, and contamination episodes undermining fragile infrastructure. In short, while there has been commendable movement forward, the SDG 6 targets remain out of reach without accelerated investments.

India's Story: Rapid Progress, Transformational Impact

The most striking story in the 2024 report is India's progress. Unlike in the early decades after Independence, when improvements in WASH were incremental and often uneven, the 21st century has seen a dramatic turnaround. Consider the contrast: between 1947 and 2000, open defecation declined only gradually, with hundreds of millions still without access to toilets. In the last two decades, however, India has reduced open defecation by over 676 million people (2000-2024)-one of the largest behaviour and infrastructure shifts in human history.

Drinking Water

According to JMP 2024, 76.4 per cent of India's population now has access to safely managed drinking water services, up from about 37 per cent in 2000. Urban coverage is exceptionally high (83 per cent), though rural areas (53 per cent) still lag. Importantly, India is among the few countries to achieve a 15 percentage point gain in safely managed drinking water in less than a decade.

This improvement means that tens of millions of households now access water on premises, free from contamination, and available when needed. The health implications are profound: reduced diarrheal disease, lower under-five mortality, and better nutritional outcomes.

Sanitation

The transformation under the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) is equally noteworthy. By 2024, 62.8 per cent of Indians had access to safely managed sanitation services, while open defecation had fallen to 6.7 per cent nationally (11 per cent rural, <1 per cent urban). This represents a 20 percentage point reduction in less than a decade, a scale of change rarely seen in social policy.

Evidence is also emerging about its impact. A 2024 study in Nature examining toilet construction under SBM, found a significant correlation between increased toilet coverage and declines in infant mortality. It was revealed that the national sanitation programme has contributed significantly to reducing infant and under-five mortality rates across the country, averting 60,000-70,000 infant deaths annually. This validates what practitioners long believed-that sanitation is not only about dignity but is a life-saving intervention.

Hygiene

India's progress in hygiene is equally remarkable. By 2024, 89.7 per cent of households had access to basic hygiene facilities (soap and water), up from just 54 per cent in 2010. The expansion of handwashing infrastructure, partly spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, has set India on track to achieve near-universal hygiene coverage by 2030.

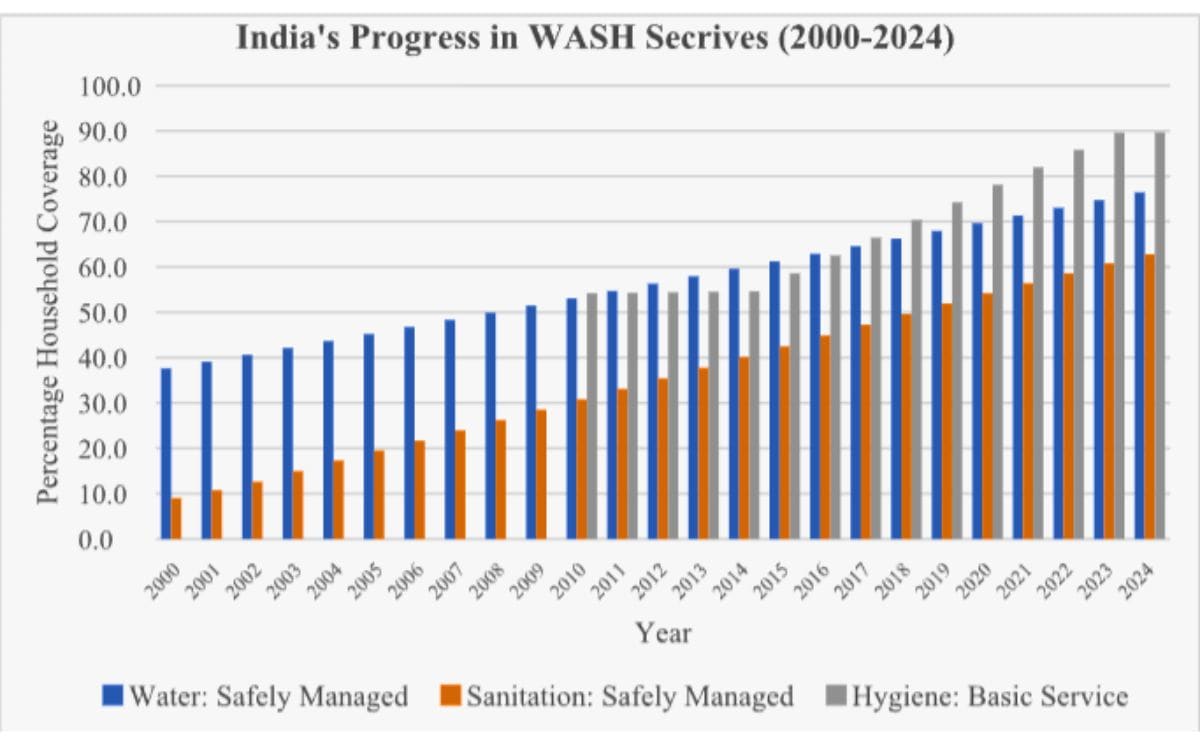

The table below captures the impressive journey India has embarked on in this century.

Here, the highest criteria for service delivery in drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene have been considered. For example, the JMP considers the highest service in drinking water as 'safely managed'. This has been defined as drinking water from an improved source that is accessible on premises, available when needed and free from faecal and priority chemical contamination.

Likewise, the gold standard in sanitation is 'safely managed sanitation', defined as the use of improved facilities that are not shared with other households and where excreta are safely disposed of in situ or removed and treated off-site. While some definitions are evolving, JMP is continually working to incorporate new criteria, such as climate-resilient WASH.

Economic Dividend

The impact of WASH investments is not limited to health; it extends to the economy. The 'Mission Critical' report (WaterAid & Vivid Economics, 2021) estimated that every rupee invested in WASH generates multiple times its value in economic returns by improving productivity, reducing health costs, and saving time, particularly for women. By reducing water collection burdens and ensuring safe sanitation, India has effectively unlocked billions of hours of productive time annually.

Let's consider only the sanitation gains since 2000. The cumulative effect is equivalent to tens of billions of dollars added to the Indian economy, through better health, higher school attendance, and increased workforce participation.

Persistent Inequalities And Gaps

Despite the progress, challenges remain. Inequalities by geography, caste, class, and gender persist. Data taken from various sources, including the JMP reports, highlights:

Rural-urban gaps: 83 per cent of urban households enjoy safely managed drinking water versus only 53 per cent in rural India.

State disparities: Hygiene coverage ranges from 96 per cent in Sikkim to just 29 per cent in Odisha, showing that national averages mask local inequities.

Treatment challenges: While septic tanks are standard (used by 75 per cent of rural and 79 per cent of urban households), only 17 per cent are connected to treatment plants. Without safe disposal, faecal sludge management risks undoing health gains.

Gendered burden: Women and girls disproportionately shoulder the challenges of inadequate WASH, including safety risks from distant water sources or lack of private toilets.

These gaps underline that while India has hurried in expanding access, ensuring safety, sustainability, and equity is the next frontier.

Policy Recommendations For Next Decade

India's achievements in WASH deserve celebration, but the next decade requires sharper focus. Based on global evidence and India's own lessons, three priority directions stand out:

1. Sustain progress through infrastructure and behavioural change: Progress in WASH can only be sustained if supported by robust infrastructure alongside behavioural transformation. India has already invested nearly $100 billion in sanitation and drinking water, yielding visible improvements. This scale of investment must continue to achieve sustained change. Therefore, there should be a renewed commitment to Swachh Bharat Mission 3.0 and National Jal Jeevan Mission 2.0, albeit with a modified approach that prioritises long-term sustainability.

2. Deepen community participation to prevent reversals: The gains made in WASH are not permanent; without strong community ownership and local-level institutionalisation, they can easily be reversed. The JMP report itself notes reversals in several countries. India must avoid this risk by maintaining momentum through decentralisation, ensuring that panchayats, self-help groups, non-profits, and community-led organisations are at the heart of planning, monitoring, and sustaining WASH outcomes.

3. Promote research, innovation, and youth engagement: Research on the ground-level impact of WASH initiatives remains limited in India. Universities, technical institutes, and young innovators are largely disconnected from the realities of implementation. As we advance, academia, researchers, and technology developers must play a central role in assessing impact, advancing innovation, and designing context-specific solutions. Realising the massive gains of the past two decades can no longer remain solely a government mandate; it requires the intellectual and creative engagement of India's research and innovation ecosystem.

India's journey in WASH is one of the most significant social transformations of this century. From being the epicentre of open defecation two decades ago, the country has emerged as a leader in large-scale sanitation and water interventions. Yet, the 2024 JMP reminds us that progress is fragile unless inequalities are addressed and sustainability is ensured.

For India, the challenge is clear: to move from access to safely managed, equitable, and resilient WASH services. Achieving this will not only bring the country closer to SDG 6 but will also strengthen its human development profile, adding to the nation's health, dignity, and economic vitality.

(Biswanath Sinha is a senior social sector leader, and can be reached at mbiswanath@gmail.com)

Disclaimer: These are the personal opinions of the author