Hillary Rodham Clinton, at her 1969 graduation.

Hillary Clinton's moment of glory at Wellesley College came when she mounted the stage at her commencement ceremony and took on a powerful Republican U.S. senator, culminating four years of what her campaign now describes as "social-justice activism" on the burning issues of the time.

But the story not yet told is how out of character Clinton's inflammatory Wellesley speech was. At a time when the country was questioning the system, Clinton was known for working squarely within it. She was a conciliator, not a bomb thrower.

On graduation day, the onetime Goldwater Girl reinvented herself as a provocative voice speaking for her angry generation. With the national media closely following campus upheaval that spring, Clinton stole the spotlight by rebuking a Washington symbol she had helped elect. She undercut Wellesley's president, once her ally in tamping down campus unrest.

Clinton's remarks transformed her, virtually overnight, into a national symbol of student activism. Wire services blasted out her remarks, and Life magazine featured her photo, dressed in bold striped bell-bottoms. Clinton soon caught the attention of leading figures of the left, including civil rights activist Vernon Jordan and her future mentor, Children's Defense Fund founder Marian Wright Edelman, and by the fall, when she entered Yale Law School and met her future husband, Bill, her name was well known.

Clinton's speech was an early illustration of political instinct, the ability to sense the moment for a strategic strike. Her performance surprised everyone, even her close friends.

"We're not interested in social reconstruction," she corrected the speaker, Sen. Edward Brooke of Massachusetts. "It's human reconstruction."

Her impromptu attack was over in a flash, and Wellesley President Ruth Adams set out to repair the damage.

Adams fired off a letter to Brooke, then the nation's highest-ranking black elected official, apologizing for Clinton's intemperate remarks.

"Courtesy is not one of the stronger virtues of the young," she wrote Brooke on June 5, 1969, in a letter The Washington Post recently discovered in his archived papers. "Scoring debater's points seems, on occasion, to have higher standing."

How do we harness such "youthful passion," Adams asked, "without destroying the basic fabric of our democratic society?"

The senator, who died in 2015, later remembered Clinton in his autobiography as a woman who "knew where she wanted to go and how she wanted to get there."

Brooke's speechwriter, Alton Frye, said the senator took note of the young student government president, bold enough to confront him.

"We looked back on her impromptu remarks," said Frye, "as an early indicator of the powerful ambition at the center of her personality."

---

Clinton's parents - she was known then as Hillary Rodham - dropped her off at tranquil Wellesley College in the fall of 1965. Hugh and Dorothy Rodham from placid Park Ridge, Illinois, saw the campus - with its weekend curfews and restrictions on male visitors - as "a place where we would be safe," recalled Clinton's friend, Constance Hoenk Shapiro.

Clinton thrived in the females-only setting. She became active in the Young Republicans and urged students to help Brooke become the first African-American elected to the Senate since Reconstruction. "The girl who doesn't want to go out and shake hands can type letters or do general office work," she told the Wellesley newspaper.

Clinton held up Barry Goldwater, the Arizona senator who lost the 1964 presidential race, as an icon. Upperclassman Laura Grosch, a free-spirited artist, remembered getting a Goldwater talk as Clinton sat to have her portrait painted, a $30 purchase she planned to send to her mother.

"I talked a lot about women's rights, civil rights, Vietnam; she was so for Goldwater," Grosch said.

The campus was alive with student protests, reflecting the growing unrest of the times. There were a string of student petitions demanding greater racial diversity in enrollment and faculty hiring, notices for meetings of national student protest groups and mounting local opposition to the draft and the Vietnam War.

Clinton was not the leader in any of these efforts. Her name shows up on one of the many student petitions filed in Adams' archived papers, this one challenging a dorm assignment policy that students considered racially discriminatory.

Her knack for public speaking was obvious to anyone who saw her onstage at an outdoor demonstration in her sophomore year.

The topic that day appealed to Clinton's wonkish nature. It focused on the curriculum and whether Wellesley's administration should adopt a pass/fail grading system.

"People's faces were riveted on her," said Karin Rosenthal, who photographed Clinton for the student newspaper.

"She had this formidable quality of poise, of self-control, of self-containment," which caused some resentment among the more bohemian and rebellious students, said Robert Pinsky, a former professor who was later poet laureate.

---

The 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. rocked Wellesley, as it did campuses across the country. Clinton went to a memorial rally in Boston and contacted one of the five African-American students in her class to offer sympathies.

Wellesley's black students were leading the way in social activism, using a newly formed group called Ethos to pressure the administration and the board. Their efforts - including a threatened hunger strike - helped ramp up Wellesley's student recruiting at historically black colleges and ensure minority representation on academic committees.

Ethos's first leader, Karen Williamson, who made friends with Clinton in her freshman year, said Clinton consistently supported the group, which had wide backing among the students. Williamson said she has "no specific memories" of Clinton's involvement in its causes.

Clinton climbed student government leadership ranks focused on educational reform. The interest occasionally took her off campus, where she met other promising student leaders. One was Robert Reich, then at Dartmouth.

"She was not a rebel or a student revolutionary," said Reich, who joined Bill Clinton's administration as secretary of labor. Hillary's shared interest in curriculum change, he said, "was pretty tame stuff."

But Clinton's worldview was broadening. She went with her friend Shapiro to Boston, where a Harvard professor ran a homework center for inner-city children.

But Clinton's worldview was broadening. She went with her friend Shapiro to Boston, where a Harvard professor ran a homework center for inner-city children.

Clinton, her friend said, became "more aware of the importance of social action in shaping the minds of those in decision-making positions."

By Clinton's junior year, her friends in the Wellesley Young Republicans sensed they were losing a champion. "I saw it in discussions in political science classes," said Rhea Kemble Dignam, then a fellow club member. The classes debated a wide range of issues including America's role overseas and domestic chaos. "It was just clear to me that her political philosophy had changed," Dignam said.

In bucolic Wellesley, student protests spilled from campus into the village. Students carried signs demanding fair housing, black economic power and a common theme: "Get Out of Vietnam NOW."

Back at Clinton's dorm, Stone-Davis, the war had particular resonance. Down the hall from Clinton's spacious suite, a fellow student was corresponding with a brother fighting in Vietnam. Clinton and a group of friends who have remained close ever since rallied around the dorm mate, and Clinton joined expeditions to New Hampshire to support Democrat Eugene McCarthy's anti-war campaign.

But she did not lead the protest.

"There were different strains of anti-war opinion," said Ellen DuBois, now a professor of gender studies at UCLA, who was devising draft-avoidance strategies. "Hillary was working within a more electoral mode."

Clinton sometimes spent long evenings discussing race and poverty with Grosch and others. As a student leader, she took on a time-consuming role considered a stepping stone to the presidency, leading the "Vil Juniors." She and other juniors helped orient freshmen in Wellesley's rules and traditions.

"She was determined to make something of herself," recalled Sarah Malino. "She was choosing leadership position after leadership position."

Clinton ran for student government president against two candidates - a member of Ethos and the junior class president. Clinton's connections among younger students paid off. She won.

Even then, Clinton "was a person who got what the system was," recalled Eleanor "Eldie" Acheson, granddaughter of former secretary of state Dean Acheson.

Clinton circulated a note asking students for ideas. She wanted to create an "activist forum from which no ideas are excluded."

Her conciliatory style was too soft for some students who wanted more radical change. "Hillary worked with the deans," recalled classmate Dorothy Devine, "rather than circumventing the rules."

In her new role, Clinton met regularly with Adams and Wellesley's vice president, Philip M. Phibbs, a political science professor. She was an "honest broker" for the students, Phibbs recalled, but didn't rock the boat.

"She was concerned about the college," Phibbs said. "She didn't want to see student concerns articulated in a way that was disruptive of the college."

---

Clinton's politics gelled after a summer internship on Capitol Hill in 1968, according to her thesis adviser, Alan Schechter, a Clinton supporter.

Clinton says in her autobiography that she "objected to no avail" when she was assigned to the House Republican Conference, led by her home state's Republican Rep. Melvin Laird, a hawk on Vietnam. Phibbs and Schechter recall no such strong opposition.

"She was still thinking and searching," Phibbs said.

In Washington, Clinton befriended a GOP conference member, New York Republican congressman Charles Goodell. He invited Clinton and other interns to go to the GOP presidential convention in Miami to rally support for New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, a long-shot against front-runner Richard Nixon.

Clinton was disappointed when Nixon, her father's favorite, won the nomination without supporting troop reductions in Vietnam. She returned home to Park Ridge and drove with a friend to Chicago to get a glimpse of the mayhem surrounding the Democratic convention.

As senior year began, Clinton had concluded that the Republican Party was drifting too far to the right. She marched into Schechter's office and announced her intention to devote herself to social equality. Schecter said she was "the most passionate I've ever seen her."

Schechter helped her shape a thesis comparing the effectiveness of intervention models - the grass-roots approach espoused by Saul Alinsky versus top-down government support. Clinton said later that she had a "fundamental disagreement" with Alinsky's theory that change could come only from outside the system.

Clinton interviewed Alinsky twice to produce her thesis, "There is Only the Fight." Schechter gave the paper an "A," and she noted in her paper that Alinsky offered her a job working at his Chicago foundation, which she declined to go to law school.

But Clinton's focus on the social activist later proved controversial. In the early 1990s, Schechter was camping in Montana when the White House contacted him and asked him to help keep the first lady's early academic work under wraps.

Schechter viewed the move as a mistake - "If you hide it people will use it against you," he said he argued to the staffer.

Ever since, the thesis has been cast by Clinton's critics - including Ben Carson at the 2016 GOP convention in Cleveland - as evidence of Clinton's early association with radicals.

To Schechter, Clinton's thesis showed an emerging policy junkie, not necessarily a budding politician.

He was among those surprised when she took the stage at commencement and showed she could "sense the mood of the audience (and) nudge it in a particular direction."

---

Brooke was "overwhelmingly" chosen by the Class of 1969 to serve as commencement speaker, Adams told him in an invitation letter.

In his talk, Brooke "wanted to encourage and recognize that they should be free spirits," speechwriter Frye said, "but realize that there has to be an anchor of order, in order to make liberty durable and productive."

As commencement neared, Acheson led the effort that would win Clinton a place on the stage.

Adams initially refused to allow the first-ever student speaker, but Acheson argued that students had earned a voice. In her autobiography, Clinton suggested she tipped the balance by meeting with Adams one-on-one.

"She didn't see it as her speech," said Jan Piercy, a close friend who later worked in Bill Clinton's administration. Piercy recalled Clinton tapping fellow students on the shoulder, asking "What should I say?"

"She was on a listening tour," said friend Ann Rosewater. Responses poured in.

Piercy recalled seeing Clinton surrounded in her dorm room by "a skirt of paper notes." And she was like, 'Oh my God, how am I going to pull all this together?' "

Clinton said she pulled an all-nighter to write her prepared remarks. She showed Schecter a draft and asked Acheson for comment. But not Adams.

Over lunch, the president tried to get Clinton to share, but Clinton wouldn't budge. Known for her wry wit, she later entertained friends by re-enacting her meeting with the starchy Adams, recalled Mary Shanley, a Wellesley alumna who visited Stone-Davis.

Clinton by that point had little to lose. Her time at Wellesley was wrapping up, and she had already been admitted to Yale Law School.

"She was engaged in a battle of political wit," Shanley said.

---

More than 2,000 people gathered on May 31, 1969, for the college's 91st annual commencement. The program doesn't mention a student speaker, perhaps because the idea blossomed so late.

Brooke gave what some considered a patronizing speech on student unrest. Clinton said in her autobiography that he seemed out of touch with the times. He illustrated social progress by citing a national decline in poverty rates, urging students not to "mistake the vigor of protest for the value of accomplishment."

Adams then introduced Clinton as "cheerful, good humored, good company, and a good friend to all of us."

Clinton took the stage. With a dramatic flourish, she set aside the text she had scrambled to prepare and turned to look at Brooke.

"We're not in the positions yet of leadership and power," she began. "But we do have that indispensable element of criticizing and constructive protest." She chastised Brooke for reducing poverty to a statistic. "That's a percentage," she said.

Clinton's unexpected slap at Brooke (which is cut from a recording Wellesley posted online) was forceful.

Acheson watched from the front row. She avoided looking at Adams, knowing the president would feel betrayed.

When Clinton finished, the applause lasted 34 seconds, according to an audio recording. Students rose in an ovation. "We were proud of her and proud of ourselves," Acheson said.

Some parents were miffed - and told their daughters so. Clinton suggested in her autobiography that Adams retaliated that day by having a security guard hide her glasses and clothes when she went for a dip in Lake Waban, the campus swimming spot.

Afterward, Clinton classmate Donna Ecton wrote Brooke to assure him that "the majority" of seniors were "dismayed by Hillary Rodham's rude rebuttal." An alumna wrote criticizing Clinton's self-promotion: "If she was looking to have her picture on the front page," the donor wrote, "she got it."

Clinton was already on a path to national recognition. But there's one small sign - discovered years later in Life magazine's archives - that she worried about how she might be perceived.

Life's photographer attached a note to his files after visiting Clinton in Park Ridge.

The young student leader, now cast as an outspoken symbol of her generation, was "quite concerned" it read, "that it be made clear she was not attacking Senator Brooke personally."

© 2016 The Washington Post

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

But the story not yet told is how out of character Clinton's inflammatory Wellesley speech was. At a time when the country was questioning the system, Clinton was known for working squarely within it. She was a conciliator, not a bomb thrower.

On graduation day, the onetime Goldwater Girl reinvented herself as a provocative voice speaking for her angry generation. With the national media closely following campus upheaval that spring, Clinton stole the spotlight by rebuking a Washington symbol she had helped elect. She undercut Wellesley's president, once her ally in tamping down campus unrest.

Clinton's remarks transformed her, virtually overnight, into a national symbol of student activism. Wire services blasted out her remarks, and Life magazine featured her photo, dressed in bold striped bell-bottoms. Clinton soon caught the attention of leading figures of the left, including civil rights activist Vernon Jordan and her future mentor, Children's Defense Fund founder Marian Wright Edelman, and by the fall, when she entered Yale Law School and met her future husband, Bill, her name was well known.

Clinton's speech was an early illustration of political instinct, the ability to sense the moment for a strategic strike. Her performance surprised everyone, even her close friends.

"We're not interested in social reconstruction," she corrected the speaker, Sen. Edward Brooke of Massachusetts. "It's human reconstruction."

Her impromptu attack was over in a flash, and Wellesley President Ruth Adams set out to repair the damage.

Adams fired off a letter to Brooke, then the nation's highest-ranking black elected official, apologizing for Clinton's intemperate remarks.

"Courtesy is not one of the stronger virtues of the young," she wrote Brooke on June 5, 1969, in a letter The Washington Post recently discovered in his archived papers. "Scoring debater's points seems, on occasion, to have higher standing."

How do we harness such "youthful passion," Adams asked, "without destroying the basic fabric of our democratic society?"

The senator, who died in 2015, later remembered Clinton in his autobiography as a woman who "knew where she wanted to go and how she wanted to get there."

Brooke's speechwriter, Alton Frye, said the senator took note of the young student government president, bold enough to confront him.

"We looked back on her impromptu remarks," said Frye, "as an early indicator of the powerful ambition at the center of her personality."

---

Clinton's parents - she was known then as Hillary Rodham - dropped her off at tranquil Wellesley College in the fall of 1965. Hugh and Dorothy Rodham from placid Park Ridge, Illinois, saw the campus - with its weekend curfews and restrictions on male visitors - as "a place where we would be safe," recalled Clinton's friend, Constance Hoenk Shapiro.

Clinton thrived in the females-only setting. She became active in the Young Republicans and urged students to help Brooke become the first African-American elected to the Senate since Reconstruction. "The girl who doesn't want to go out and shake hands can type letters or do general office work," she told the Wellesley newspaper.

Clinton held up Barry Goldwater, the Arizona senator who lost the 1964 presidential race, as an icon. Upperclassman Laura Grosch, a free-spirited artist, remembered getting a Goldwater talk as Clinton sat to have her portrait painted, a $30 purchase she planned to send to her mother.

"I talked a lot about women's rights, civil rights, Vietnam; she was so for Goldwater," Grosch said.

The campus was alive with student protests, reflecting the growing unrest of the times. There were a string of student petitions demanding greater racial diversity in enrollment and faculty hiring, notices for meetings of national student protest groups and mounting local opposition to the draft and the Vietnam War.

Clinton was not the leader in any of these efforts. Her name shows up on one of the many student petitions filed in Adams' archived papers, this one challenging a dorm assignment policy that students considered racially discriminatory.

Her knack for public speaking was obvious to anyone who saw her onstage at an outdoor demonstration in her sophomore year.

The topic that day appealed to Clinton's wonkish nature. It focused on the curriculum and whether Wellesley's administration should adopt a pass/fail grading system.

"People's faces were riveted on her," said Karin Rosenthal, who photographed Clinton for the student newspaper.

"She had this formidable quality of poise, of self-control, of self-containment," which caused some resentment among the more bohemian and rebellious students, said Robert Pinsky, a former professor who was later poet laureate.

---

The 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. rocked Wellesley, as it did campuses across the country. Clinton went to a memorial rally in Boston and contacted one of the five African-American students in her class to offer sympathies.

Wellesley's black students were leading the way in social activism, using a newly formed group called Ethos to pressure the administration and the board. Their efforts - including a threatened hunger strike - helped ramp up Wellesley's student recruiting at historically black colleges and ensure minority representation on academic committees.

Ethos's first leader, Karen Williamson, who made friends with Clinton in her freshman year, said Clinton consistently supported the group, which had wide backing among the students. Williamson said she has "no specific memories" of Clinton's involvement in its causes.

Clinton climbed student government leadership ranks focused on educational reform. The interest occasionally took her off campus, where she met other promising student leaders. One was Robert Reich, then at Dartmouth.

"She was not a rebel or a student revolutionary," said Reich, who joined Bill Clinton's administration as secretary of labor. Hillary's shared interest in curriculum change, he said, "was pretty tame stuff."

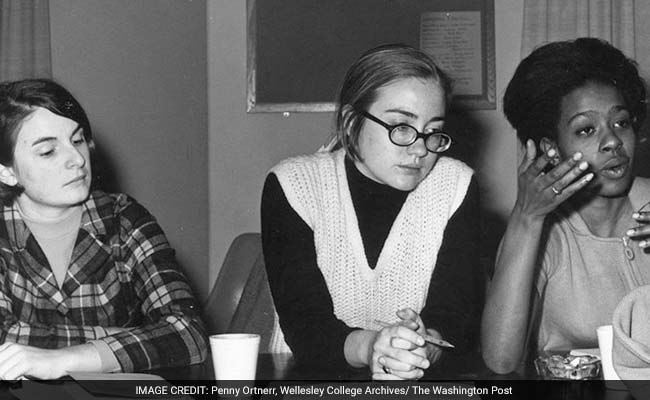

Hillary Rodham (center) at a panel featuring candidates for Wellesley College government president.

Clinton, her friend said, became "more aware of the importance of social action in shaping the minds of those in decision-making positions."

By Clinton's junior year, her friends in the Wellesley Young Republicans sensed they were losing a champion. "I saw it in discussions in political science classes," said Rhea Kemble Dignam, then a fellow club member. The classes debated a wide range of issues including America's role overseas and domestic chaos. "It was just clear to me that her political philosophy had changed," Dignam said.

In bucolic Wellesley, student protests spilled from campus into the village. Students carried signs demanding fair housing, black economic power and a common theme: "Get Out of Vietnam NOW."

Back at Clinton's dorm, Stone-Davis, the war had particular resonance. Down the hall from Clinton's spacious suite, a fellow student was corresponding with a brother fighting in Vietnam. Clinton and a group of friends who have remained close ever since rallied around the dorm mate, and Clinton joined expeditions to New Hampshire to support Democrat Eugene McCarthy's anti-war campaign.

But she did not lead the protest.

"There were different strains of anti-war opinion," said Ellen DuBois, now a professor of gender studies at UCLA, who was devising draft-avoidance strategies. "Hillary was working within a more electoral mode."

Clinton sometimes spent long evenings discussing race and poverty with Grosch and others. As a student leader, she took on a time-consuming role considered a stepping stone to the presidency, leading the "Vil Juniors." She and other juniors helped orient freshmen in Wellesley's rules and traditions.

"She was determined to make something of herself," recalled Sarah Malino. "She was choosing leadership position after leadership position."

Clinton ran for student government president against two candidates - a member of Ethos and the junior class president. Clinton's connections among younger students paid off. She won.

Even then, Clinton "was a person who got what the system was," recalled Eleanor "Eldie" Acheson, granddaughter of former secretary of state Dean Acheson.

Clinton circulated a note asking students for ideas. She wanted to create an "activist forum from which no ideas are excluded."

Her conciliatory style was too soft for some students who wanted more radical change. "Hillary worked with the deans," recalled classmate Dorothy Devine, "rather than circumventing the rules."

In her new role, Clinton met regularly with Adams and Wellesley's vice president, Philip M. Phibbs, a political science professor. She was an "honest broker" for the students, Phibbs recalled, but didn't rock the boat.

"She was concerned about the college," Phibbs said. "She didn't want to see student concerns articulated in a way that was disruptive of the college."

---

Clinton's politics gelled after a summer internship on Capitol Hill in 1968, according to her thesis adviser, Alan Schechter, a Clinton supporter.

Clinton says in her autobiography that she "objected to no avail" when she was assigned to the House Republican Conference, led by her home state's Republican Rep. Melvin Laird, a hawk on Vietnam. Phibbs and Schechter recall no such strong opposition.

"She was still thinking and searching," Phibbs said.

In Washington, Clinton befriended a GOP conference member, New York Republican congressman Charles Goodell. He invited Clinton and other interns to go to the GOP presidential convention in Miami to rally support for New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, a long-shot against front-runner Richard Nixon.

Clinton was disappointed when Nixon, her father's favorite, won the nomination without supporting troop reductions in Vietnam. She returned home to Park Ridge and drove with a friend to Chicago to get a glimpse of the mayhem surrounding the Democratic convention.

As senior year began, Clinton had concluded that the Republican Party was drifting too far to the right. She marched into Schechter's office and announced her intention to devote herself to social equality. Schecter said she was "the most passionate I've ever seen her."

Schechter helped her shape a thesis comparing the effectiveness of intervention models - the grass-roots approach espoused by Saul Alinsky versus top-down government support. Clinton said later that she had a "fundamental disagreement" with Alinsky's theory that change could come only from outside the system.

Clinton interviewed Alinsky twice to produce her thesis, "There is Only the Fight." Schechter gave the paper an "A," and she noted in her paper that Alinsky offered her a job working at his Chicago foundation, which she declined to go to law school.

But Clinton's focus on the social activist later proved controversial. In the early 1990s, Schechter was camping in Montana when the White House contacted him and asked him to help keep the first lady's early academic work under wraps.

Schechter viewed the move as a mistake - "If you hide it people will use it against you," he said he argued to the staffer.

Ever since, the thesis has been cast by Clinton's critics - including Ben Carson at the 2016 GOP convention in Cleveland - as evidence of Clinton's early association with radicals.

To Schechter, Clinton's thesis showed an emerging policy junkie, not necessarily a budding politician.

He was among those surprised when she took the stage at commencement and showed she could "sense the mood of the audience (and) nudge it in a particular direction."

---

Brooke was "overwhelmingly" chosen by the Class of 1969 to serve as commencement speaker, Adams told him in an invitation letter.

In his talk, Brooke "wanted to encourage and recognize that they should be free spirits," speechwriter Frye said, "but realize that there has to be an anchor of order, in order to make liberty durable and productive."

As commencement neared, Acheson led the effort that would win Clinton a place on the stage.

Adams initially refused to allow the first-ever student speaker, but Acheson argued that students had earned a voice. In her autobiography, Clinton suggested she tipped the balance by meeting with Adams one-on-one.

"She didn't see it as her speech," said Jan Piercy, a close friend who later worked in Bill Clinton's administration. Piercy recalled Clinton tapping fellow students on the shoulder, asking "What should I say?"

"She was on a listening tour," said friend Ann Rosewater. Responses poured in.

Piercy recalled seeing Clinton surrounded in her dorm room by "a skirt of paper notes." And she was like, 'Oh my God, how am I going to pull all this together?' "

Clinton said she pulled an all-nighter to write her prepared remarks. She showed Schecter a draft and asked Acheson for comment. But not Adams.

Over lunch, the president tried to get Clinton to share, but Clinton wouldn't budge. Known for her wry wit, she later entertained friends by re-enacting her meeting with the starchy Adams, recalled Mary Shanley, a Wellesley alumna who visited Stone-Davis.

Clinton by that point had little to lose. Her time at Wellesley was wrapping up, and she had already been admitted to Yale Law School.

"She was engaged in a battle of political wit," Shanley said.

---

More than 2,000 people gathered on May 31, 1969, for the college's 91st annual commencement. The program doesn't mention a student speaker, perhaps because the idea blossomed so late.

Brooke gave what some considered a patronizing speech on student unrest. Clinton said in her autobiography that he seemed out of touch with the times. He illustrated social progress by citing a national decline in poverty rates, urging students not to "mistake the vigor of protest for the value of accomplishment."

Adams then introduced Clinton as "cheerful, good humored, good company, and a good friend to all of us."

Clinton took the stage. With a dramatic flourish, she set aside the text she had scrambled to prepare and turned to look at Brooke.

"We're not in the positions yet of leadership and power," she began. "But we do have that indispensable element of criticizing and constructive protest." She chastised Brooke for reducing poverty to a statistic. "That's a percentage," she said.

Clinton's unexpected slap at Brooke (which is cut from a recording Wellesley posted online) was forceful.

Acheson watched from the front row. She avoided looking at Adams, knowing the president would feel betrayed.

When Clinton finished, the applause lasted 34 seconds, according to an audio recording. Students rose in an ovation. "We were proud of her and proud of ourselves," Acheson said.

Some parents were miffed - and told their daughters so. Clinton suggested in her autobiography that Adams retaliated that day by having a security guard hide her glasses and clothes when she went for a dip in Lake Waban, the campus swimming spot.

Afterward, Clinton classmate Donna Ecton wrote Brooke to assure him that "the majority" of seniors were "dismayed by Hillary Rodham's rude rebuttal." An alumna wrote criticizing Clinton's self-promotion: "If she was looking to have her picture on the front page," the donor wrote, "she got it."

Clinton was already on a path to national recognition. But there's one small sign - discovered years later in Life magazine's archives - that she worried about how she might be perceived.

Life's photographer attached a note to his files after visiting Clinton in Park Ridge.

The young student leader, now cast as an outspoken symbol of her generation, was "quite concerned" it read, "that it be made clear she was not attacking Senator Brooke personally."

© 2016 The Washington Post

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world