There is therefore an overall mood of economic disenchantment that can only be countered by the persona of Narendra Modi. But then, he is no longer the Chief Minister, and the man holding that post, Vijay Rupani, does not register as a leader in the state. Therefore, questions remain about how effectively the energetic Modi campaign can shore up the fort in the last lap of the campaign.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a rally in Jamnagar, Gujarat (PTI)

Three Election Models

There are distinct types of electoral verdicts in India: the smart arithmetical model where there one party manages more than others in the first-past-the-post system as the contest between the others divides or splits votes in favour of the winner. This formula, well-oiled by BJP president Amit Shah, cannot be applied to Gujarat where the contest is mostly between two parties, the BJP and Congress.

It's also worth noting that unlike the plight of the Congress in a state such as Uttar Pradesh, where it has been fourth place for some time, in Gujarat, it has actually held on to around 40 per cent of the vote on an average (38.93 in the last assembly poll in 2012). Contrary to media perceptions that the Congress is distant history in Gujarat, in reality, it does have a starting bloc.

The second electoral model is the "wave" election, the sort which powered Narendra Modi to power repeatedly in Gujarat and in India in 2014 and the 2015 Delhi assembly election, where voters were thoroughly enchanted with Arvind Kejriwal and his AAP. This is not a wave election in Gujarat. Indeed, some comparisons between Hardik Patel and Kejriwal have been made, but they do not stand the scrutiny of analysis. True, Hardik is a disrupter, but he only speaks for one caste that makes up 13.8 per cent of the population. His language is crude if effective. At 24, Hardik is too young to contest himself and the experiment to channelize a new movement's support towards an old party (in this case the Congress) will be worth analyzing once the dust has settled and the verdict is out.

Hardik Patel at a rally in Patidar stronghold Morbi in Gujarat

The third model of Indian elections is arguably the most common: when people don't vote for the challenger, but become indifferent to supporting the incumbent regime. The BJP's performance hinges on this: are there enough people who would still swear by the party and respond to Modi's emotional pitch? Would people stay at home if not inspired to vote, but stop short of voting against the BJP? Or would people actually go out and caste a vote for the Congress, something that seems unlikely.

Poor Party, Rich Leaders

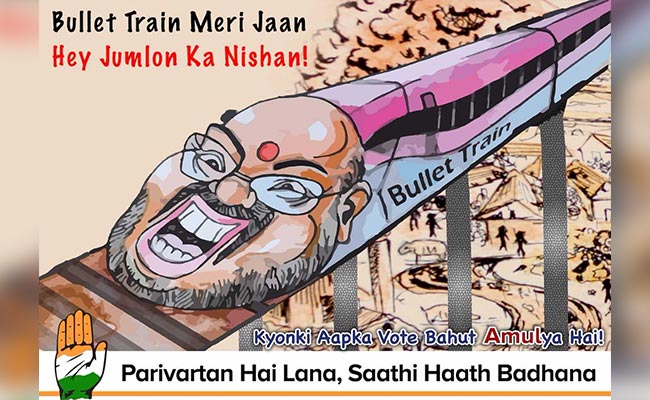

Rahul Gandhi is giving one of the more credible political performances of his life in Gujarat. The party is working through autonomous units scattered across Gujarat; some committed old party hands have been grafted from the central pool to work in seats seen as winnable; some volunteers have come up with fresh ideas such as the irreverent Amul-style campaigns designed for Surat city.

Congress party has designed Amul-style campaigns for Surat city

The BJP conversely keeps the faith with those who get to fight as its contenders. It has an organized central pool of funds and established financial systems that kick in for each election. There is no ad hoc-ism about finances. A lot of campaign material comes from the central party command, and all the promised money has reached candidates in due allotments. The budget for each seat (about 2 crores according to candidates) is far more than the Congress allocation (about 25 lakhs for a candidate who's considered a sure shot).

Still, elections are also determined by chemistry. What does worry the BJP is that when there is the potential rupture of its base on caste lines, none of its identity pitches appear to be gaining traction on the ground. It's also true that these things are hard to measure. When the PM refers to the "Aurangzeb Raj" of the Congress, he is pressing a subliminal button and suggesting that were the BJP to go, Muslim rule by proxy would return. The pattern of communalism that has determined a slice of Gujarat's history has a particular psychology. Although Muslims were the victims of the 2002 riots, people still express "fear" of the community. Such emotions are not central to this election, but do lie beneath the surface.

The greater secret weapon that Modi has in 2017 is the women of Gujarat. Even when jobless young men have become restive and some may be in the mood to smash the old model, women of all ages are more inclined towards the PM. During his reign, the urban centres of the state became and remain safer for women than some other parts of India. Modi still has a lot going for him, but he also faces a genuine challenge, something that should ultimately be seen as being healthy for Indian democracy.

(Saba Naqvi is a journalist and an author.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.