- The 1916 Lucknow Pact united the Congress and Muslim League with separate electorates for Muslims

- The pact ensured minorities had a real stake and blocked legislation opposed by most community reps

- Bal Gangadhar Tilak supported the pact, urging Hindu-Muslim unity against British colonial rule

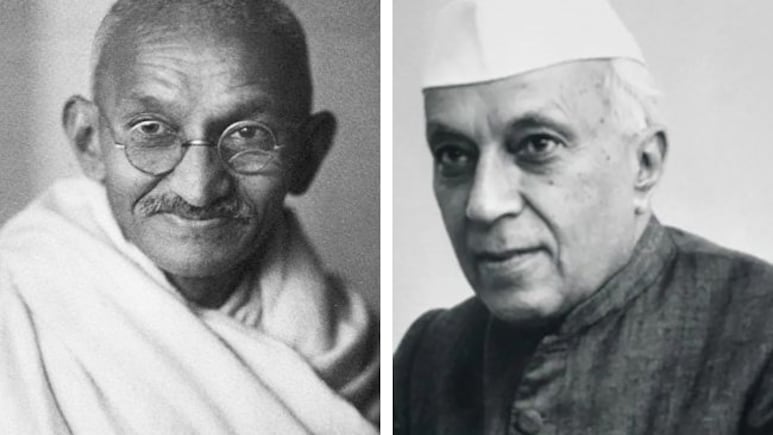

In the winter of 1916, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru met for the first time at Lucknow's Charbagh railway station. The two leaders were in the city for the 31st session of the Indian National Congress. It concluded with the historic Lucknow Pact.

Mr Gandhi was then on the fringes of Indian politics, and Mr Nehru was a restless young leader, impatient for change. The Congress session they attended together was a turning point for the national movement.

Also Read: Royal Indian Navy Mutiny Of 1946: The Naval Revolt That Shook British Rule

The Political Winds Before Lucknow

During the First World War, Britain sought Indian support, hinting at reforms. In 1914, Bal Gangadhar Tilak returned from six years in Mandalay prison, determined that Hindu-Muslim unity was key to Swaraj.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah, in both the Congress and the Muslim League, was hailed as the "ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity." Their partnership would forge the historic Lucknow Pact.

Also Read: "Do or Die": Mahatma Gandhi's Call That Sparked India's Final Push For Freedom

The Lucknow Pact Of 1916

On December 26, 1916, the Congress and the Muslim League held their sessions simultaneously in Lucknow. Mr Jinnah presided over the League, Ambika Charan Mazumdar over the Congress, with Annie Besant's Home Rule League also in session.

The pact granted Muslims separate electorates, over-represented in Hindu-majority provinces and under-represented in Muslim-majority ones. It also ensured that no legislation affecting a particular community could pass if three-fourths of that community's representatives opposed it.

Its core achievement was uniting Congress and the Muslim League, and giving minorities a real stake in governance.

Also Read: Direct Action Day: Spark That Triggered Communal Violence During Partition

Tilak's Tilak On The Lucknow Pact

Mr Tilak championed the pact in the Congress despite resistance from leaders like Madan Mohan Malaviya, BS Moonje, and Tej Bahadur Sapru.

At the Home Rule League session, he said, "There is a feeling among the Hindus that too much has been given to the Muslims. As a Hindu, I have no objection to making this concession... We cannot rise from our present intolerable condition without the aid of the Muslims."

Mr Tilak reasoned that the "triangular" struggle between Hindus, Muslims, and the British had to become a "two-way" fight between Indians and colonial power.

Mr Tilak's newspaper 'Kesari' hailed the pact as "worthy of being written with golden letters," declaring that "Caste and creed distinctions, differences of opinion, personal jealousies... were finally drowned in the waters of Gomati."

Also Read: Paika Rebellion: India's Fight Against Colonial Rule, Decades Before 1857

Why The Pact Failed

The Lucknow Pact's promise faded quickly. The 1919 Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms ignored its demands, and Mr Tilak's death in 1920 removed a key champion.

Mr Gandhi's rise brought mass, non-violent movements, which Mr Jinnah opposed, especially the Mahatma's support for the Khilafat Movement. Their differences led Mr Jinnah to leave the Congress the same year.

Although Mr Gandhi valued Hindu-Muslim unity, he never based his politics on separate electorates. In 1932, he fasted in Yerwada Jail against the Communal Award, which granted separate electorates to the Depressed Classes, fearing it would divide society.

Mr Jinnah saw separate electorates as temporary, but without Congress-League cooperation, the pact ultimately became a historical footnote.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world