Mumbai:

Bal K. Thackeray, a newspaper cartoonist who became a powerful influence in this city by championing and stoking the grievances of the native population and Hindus against outsiders and Muslims, died Saturday at his home in Mumbai. He was 86.

The cause of death was a heart attack, Thackeray's doctor, Jalil Parkar, said.

Thackeray, who had described himself as an admirer of Hitler, was a formidable force in Mumbai for more than four decades even as he grew increasingly frail. Many shops, restaurants and other businesses shut down after his death was announced, as his followers prepared to mourn him and others anticipated violence by members of his right-wing and often-militant political party, the Shiv Sena. Streets out of downtown Mumbai were clogged Saturday afternoon as office workers and others rushed to get home to avoid getting caught up in any possible scuffles. Throngs of police officers were standing by and guiding traffic through busy intersections.

In New Delhi, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh appealed for "calm and sobriety during this period of loss and mourning" and cancelled a dinner with opposition lawmakers to discuss a contentious session of parliament that is scheduled to start on Thursday. In a statement, Singh lauded Thackeray's "strong leadership and extraordinary organizational skills."

Bal Keshav Thackeray was born on January 23, 1926, in the city of Pune, about 100 miles east of Mumbai, and came of age during India's struggle for freedom from Britain. His father, Keshav Sitaram Thackeray, a journalist and activist, was said to have taken the surname because he admired the English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray. The elder Thackeray became a leader of a movement to establish the state of Maharashtra for speakers of the Marathi language, a group that would become a core constituency. Mumbai, then known as Bombay and to this day the financial hub of India, became the capital of the new state.

The younger Thackeray gained fame as a cartoonist first at the daily Free Press Journal and later at his own weekly publication, Marmik. He used his cartoons to inveigh against communists and champion the cause of the Marathi manoos, or the average Marathi citizen, who he argued was losing out to south Indians, Muslims and other outsiders. In 1966, he established the Shiv Sena, or the Army of Shiva; its mascot is a snarling tiger.

In the early years of the Shiv Sena, Thackeray battled communists and their labour unions, especially in the city's large textile industry. He was supported, scholars say, by textile mill owners and the governing Congress Party because he was taking on their opponents.

But his success came in his ability to win over Marathi-speaking working- and middle-class Hindus. Thackeray did so by arguing that Muslims and people from other parts of India had unfairly cornered the city's jobs, resources and wealth. He also argued that outsiders should be forced out and others should be barred from coming.

He and his followers often invoked and drew their legitimacy from Shivaji, a 17th-century king of the Maratha kingdom of western India who frequently battled and defeated the Mughal Empire that dominated northern India.

"He referred to the injustices, real or imagined, suffered by the Marathi speakers in order to constitute them as the only legitimate 'people,"' Gyan Prakash, a history professor at Princeton University, wrote in his 2010 book "Mumbai Fables." "The claim was that a part of society, the oppressed underdogs, was its whole; the Marathi manoos was the sum total of the community."

Supporters say Thackeray gave voice to Marathi speakers who had been taken for granted by national politicians, often from northern India. Much of Mumbai's corporate and cultural elite is made up of Indians from other parts of the country who are more comfortable speaking English. Thackeray's party also won the support of Mumbai residents by setting up branch offices in most neighbourhoods that, analysts say, were efficient at resolving conflicts and complaints about municipal services.

While Thackeray never held elected office, his political party and its allies governed the state from 1995 to 1999 and have been in charge of Mumbai's city government for more than 16 years. While his party held power at the state level, Bombay was renamed Mumbai after a fishing village that predated the Portuguese colonization of the seven islands that would become the city.

Thackeray came to dominate the city in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Hindu-Muslim tensions were high. Critics say that he took advantage of the religious strains, particularly the destruction of a 12th-century mosque in northern India by Hindu extremists in 1992, to consolidate power. Days after the destruction, riots broke out across Mumbai, and over two months, about 1,000 people were killed in the city, most of them Muslims.

An inquiry into the riots by two retired judges determined that Thackeray and his followers had provoked the unrest. Yet he was never prosecuted for that or any of the other numerous violent episodes involving the Shiv Sena. Analysts and Thackeray himself have said that he was simply too powerful to be challenged.

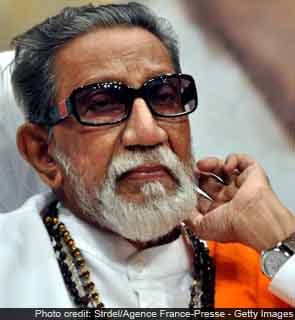

Thackeray, a short man who often wore big sunglasses, sported a full beard and draped himself in saffron-coloured clothes favoured by right-wing Hindus, was often quixotic and hard to label. For instance, even as dating became more acceptable in India, he opposed the celebration of Valentine's Day as "alien to our culture," and members of his party attacked shops and people who celebrated the day. Yet, he welcomed Michael Jackson's 1996 concert tour to Mumbai with gusto and called the singer a "great artist." He also relished drinking Heineken beer and wine and was frequently photographed with a cigar or pipe.

People who met him said he came across as charming and funny, and was engaged in the arts and movies. Thackeray's death could create a struggle for power in Mumbai and Maharashtra, India's richest and most industrialized state. His son Uddhav, his designated heir, has been hospitalized twice this year for a heart condition and is considered less charismatic and influential.

Many analysts say the Shiv Sena, the second-largest party in the state after the governing Congress Party, could lose ground to Thackeray's bombastic nephew, Raj, who left the Shiv Sena in 2006 and started a rival party, the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena. Recently, Raj Thackeray was prominently photographed fetching Uddhav from the hospital after a check-up, fuelling speculation that the two sides of the family might reconcile.

In addition to Uddhav, Thackeray is survived by another son, Jaidev, and eight grandchildren. His wife, Meena, died in 1995, and his eldest son, Bindumadhav, died a year later in a car accident.

Party officials told local television networks that his followers could pay their last respects to Thackeray at Shivaji Park, the central site in Mumbai where he started his party and held many of his rallies, on Sunday before his body was cremated.

(Neha Thirani contributed reporting)

The cause of death was a heart attack, Thackeray's doctor, Jalil Parkar, said.

Thackeray, who had described himself as an admirer of Hitler, was a formidable force in Mumbai for more than four decades even as he grew increasingly frail. Many shops, restaurants and other businesses shut down after his death was announced, as his followers prepared to mourn him and others anticipated violence by members of his right-wing and often-militant political party, the Shiv Sena. Streets out of downtown Mumbai were clogged Saturday afternoon as office workers and others rushed to get home to avoid getting caught up in any possible scuffles. Throngs of police officers were standing by and guiding traffic through busy intersections.

In New Delhi, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh appealed for "calm and sobriety during this period of loss and mourning" and cancelled a dinner with opposition lawmakers to discuss a contentious session of parliament that is scheduled to start on Thursday. In a statement, Singh lauded Thackeray's "strong leadership and extraordinary organizational skills."

Bal Keshav Thackeray was born on January 23, 1926, in the city of Pune, about 100 miles east of Mumbai, and came of age during India's struggle for freedom from Britain. His father, Keshav Sitaram Thackeray, a journalist and activist, was said to have taken the surname because he admired the English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray. The elder Thackeray became a leader of a movement to establish the state of Maharashtra for speakers of the Marathi language, a group that would become a core constituency. Mumbai, then known as Bombay and to this day the financial hub of India, became the capital of the new state.

The younger Thackeray gained fame as a cartoonist first at the daily Free Press Journal and later at his own weekly publication, Marmik. He used his cartoons to inveigh against communists and champion the cause of the Marathi manoos, or the average Marathi citizen, who he argued was losing out to south Indians, Muslims and other outsiders. In 1966, he established the Shiv Sena, or the Army of Shiva; its mascot is a snarling tiger.

In the early years of the Shiv Sena, Thackeray battled communists and their labour unions, especially in the city's large textile industry. He was supported, scholars say, by textile mill owners and the governing Congress Party because he was taking on their opponents.

But his success came in his ability to win over Marathi-speaking working- and middle-class Hindus. Thackeray did so by arguing that Muslims and people from other parts of India had unfairly cornered the city's jobs, resources and wealth. He also argued that outsiders should be forced out and others should be barred from coming.

He and his followers often invoked and drew their legitimacy from Shivaji, a 17th-century king of the Maratha kingdom of western India who frequently battled and defeated the Mughal Empire that dominated northern India.

"He referred to the injustices, real or imagined, suffered by the Marathi speakers in order to constitute them as the only legitimate 'people,"' Gyan Prakash, a history professor at Princeton University, wrote in his 2010 book "Mumbai Fables." "The claim was that a part of society, the oppressed underdogs, was its whole; the Marathi manoos was the sum total of the community."

Supporters say Thackeray gave voice to Marathi speakers who had been taken for granted by national politicians, often from northern India. Much of Mumbai's corporate and cultural elite is made up of Indians from other parts of the country who are more comfortable speaking English. Thackeray's party also won the support of Mumbai residents by setting up branch offices in most neighbourhoods that, analysts say, were efficient at resolving conflicts and complaints about municipal services.

While Thackeray never held elected office, his political party and its allies governed the state from 1995 to 1999 and have been in charge of Mumbai's city government for more than 16 years. While his party held power at the state level, Bombay was renamed Mumbai after a fishing village that predated the Portuguese colonization of the seven islands that would become the city.

Thackeray came to dominate the city in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Hindu-Muslim tensions were high. Critics say that he took advantage of the religious strains, particularly the destruction of a 12th-century mosque in northern India by Hindu extremists in 1992, to consolidate power. Days after the destruction, riots broke out across Mumbai, and over two months, about 1,000 people were killed in the city, most of them Muslims.

An inquiry into the riots by two retired judges determined that Thackeray and his followers had provoked the unrest. Yet he was never prosecuted for that or any of the other numerous violent episodes involving the Shiv Sena. Analysts and Thackeray himself have said that he was simply too powerful to be challenged.

Thackeray, a short man who often wore big sunglasses, sported a full beard and draped himself in saffron-coloured clothes favoured by right-wing Hindus, was often quixotic and hard to label. For instance, even as dating became more acceptable in India, he opposed the celebration of Valentine's Day as "alien to our culture," and members of his party attacked shops and people who celebrated the day. Yet, he welcomed Michael Jackson's 1996 concert tour to Mumbai with gusto and called the singer a "great artist." He also relished drinking Heineken beer and wine and was frequently photographed with a cigar or pipe.

People who met him said he came across as charming and funny, and was engaged in the arts and movies. Thackeray's death could create a struggle for power in Mumbai and Maharashtra, India's richest and most industrialized state. His son Uddhav, his designated heir, has been hospitalized twice this year for a heart condition and is considered less charismatic and influential.

Many analysts say the Shiv Sena, the second-largest party in the state after the governing Congress Party, could lose ground to Thackeray's bombastic nephew, Raj, who left the Shiv Sena in 2006 and started a rival party, the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena. Recently, Raj Thackeray was prominently photographed fetching Uddhav from the hospital after a check-up, fuelling speculation that the two sides of the family might reconcile.

In addition to Uddhav, Thackeray is survived by another son, Jaidev, and eight grandchildren. His wife, Meena, died in 1995, and his eldest son, Bindumadhav, died a year later in a car accident.

Party officials told local television networks that his followers could pay their last respects to Thackeray at Shivaji Park, the central site in Mumbai where he started his party and held many of his rallies, on Sunday before his body was cremated.

(Neha Thirani contributed reporting)

© 2012, The New York Times News Service

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world