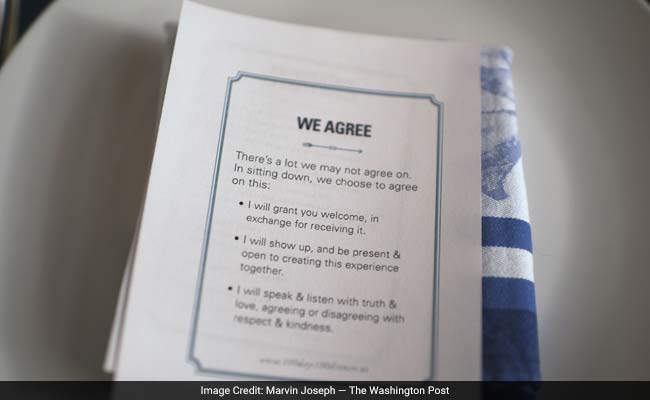

The table was set with roses, a mission statement and set of rules for debate over dinner.

- The table was set with a mission statement and set of rules for debate

- It was the 57th dinner in a project called "100 Days, 100 Dinners."

- Most participants in the past were left-leaning, organisers say

Did our AI summary help?

Let us know.

They sat in a circle around a table draped in royal blue, with flickering votives and a bouquet of pastel roses. Atop each folded napkin was a slip of paper with a printed pledge: There's a lot we may not agree on. . . .

There were eight of them. The night's two co-hosts had known each other for years; the rest were strangers. Five women, three men. Two immigrants. Three white. They kept their chatter light - "That looks delicious!" "The table is so lovely." - as they passed platters of roasted chicken and quinoa salad.

Then: "Does anyone," asked Donna Callejon, "want to explain how they wound up here?"

"Here" was the home of Marjorie Sims, who had agreed to invite half a dozen people to a potluck dinner as a small gesture of tolerance and openness in a time of unprecedented political division.

It was the 57th dinner in a project called "100 Days, 100 Dinners." The series was inspired by the 2016 election, when it became clear "that there was a deeper rupture at the heart of our democracy than a lot of people realized," said the Rev. Jennifer Bailey, founder and executive director of the Faith Matters Network, which organized the project along with two other nonprofit groups, Hollaback and The Dinner Party.

"One of the best and most ancient practices that have brought people together for millennia is this notion of breaking bread together," Bailey said. So organizers decide to host 100 dinner parties across the country during the first 100 days of Trump's presidency. Some of the gatherings would be focused on groups that feel marginalized by the new administration, Bailey said, but others would aim to create conversation "across lines of difference, whether that's racial, political, ideological, to try to humanize ourselves again." More than 600 people have attended so far.

- - -

When Gabriela Schneider first heard about the project, "I thought - yes, that is what I needed," she told her fellow guests in Sims' dining room. "I want to find people who want to find a way to come together. Because it feels like we are at war."

She paused, and smiled. "Sorry to go all zero-to-60."

Vipin Thekk, a 36-year-old native of India, said he came because "I was hoping to get to understand perspectives other than mine." The election made him realize "how much of a bubble I was in," and he wanted to know more about the people who voted for Trump.

But a dinner party isn't always the most natural way to burst a bubble.

Most of the people who have participated in "100 Days" have been left-leaning, organizers say. And among the group at Sims' home, only one was a Trump voter - and she kept this fact to herself, listening quietly as the others around her spoke first.  Callejon explained that the dinner was supposed to begin with a particular prompt: "They want us to ask about a time when you were vulnerable."

Callejon explained that the dinner was supposed to begin with a particular prompt: "They want us to ask about a time when you were vulnerable."

Crystal Yan, a 24-year-old Web designer, said she felt vulnerable when she was harassed by strange men on the street. This drew some words of dismay from Brian Hill, a bearded millennial and the lone white man at the dinner, who was saddened that she had been hassled in his own neighborhood of Mount Pleasant.

Susumu Noda, 27, a software engineer from Tokyo, said he feels self-conscious when conversations turn to politics, which he doesn't follow as closely as other Washingtonians. Sims, who is black, recalled moving back to D.C. after several years away and being stunned by the sweep of gentrification. She found herself intrigued by one new shop, but "I didn't feel comfortable going there, because everyone in line was white."

This drew the attention of Thekk. He wondered: How frequently did this kind of thing happen? "I still don't understand the complexities of race in this country," he said.

Sims said she has a "heightened radar," having watched her family deal with discrimination in her younger days: "I go places and I look around and I think, 'Is there anyone like me here?' "

But where did Somer Salomon feel vulnerable? Right here, she said - at this dinner.

"I guess," she acknowledged, resting her fork against her plate, "I'm the only person who is conservative."

The 42-year-old doctoral candidate told her fellow diners she seems to fall outside the "acceptable range of views" for Washington. "The collective feeling is that to hold different views is either uneducated, or regressive, or it comes from a place of anger - that it can't be a legitimate, thoughtful or educated difference of opinion," she said. "I feel like it's like that more and more - that there is a narrowing of what is acceptable to express."

The room fell silent for a second, save for the soft jazz percolating from the stereo speakers and a glug of wine being poured.

"Thank you for sharing that," Callejon said.

Salomon's disclosure seemed to energize the room. Schneider described how out of place she can feel within her own political tribe - particularly within the "call-out culture" of social media, she said, where people are quick to condemn anyone who disagrees with them.

"I see this a lot on my Facebook," she said. "I'm anti-PC, and I'm probably to the left of Bernie Sanders, but in that way I'm conservative, too."

Salomon nodded. "I find it very counterproductive, this idea that we can just shame people into believing the right thing."

Yan added that she's frustrated by the way too many people conduct political discussions these days, as if the object were to "win" rather than share ideas or build understanding.

"I think we are afraid to let people know when we think they've made a good point or when they might have changed our mind," she said.

Salomon agreed: "A lot of people subscribe to the idea that 'my political beliefs make me a good person.' An older way of thinking would say that what makes you a good person is your actions."

But in these unsettling times, many people are starting to take action, Callejon argued, citing "the Women's March, and people rushing to airports to help immigrants, and Black Lives Matter. People are frickin' scared. This feels really palpable to me."

Some guests nodded, others didn't; there was the vague feeling that some might have thoughts they didn't care to share. So it went through dinner - no raised voices or interruptions, and plenty of thoughtful questions, but very little treading on contentious territory.

When Callejon suggested they serve dessert because it was already 9 o'clock, everyone seemed stunned by how the evening had flown by and hailed it as a success: "I'll carry the memory that this was worthwhile," Noda said.

"I'm just really grateful that everyone was open to coming and having the conversation," Sims said. "People showed up, and that gives me hope."

Around the table, her guests raised their glasses.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)

There were eight of them. The night's two co-hosts had known each other for years; the rest were strangers. Five women, three men. Two immigrants. Three white. They kept their chatter light - "That looks delicious!" "The table is so lovely." - as they passed platters of roasted chicken and quinoa salad.

Then: "Does anyone," asked Donna Callejon, "want to explain how they wound up here?"

"Here" was the home of Marjorie Sims, who had agreed to invite half a dozen people to a potluck dinner as a small gesture of tolerance and openness in a time of unprecedented political division.

It was the 57th dinner in a project called "100 Days, 100 Dinners." The series was inspired by the 2016 election, when it became clear "that there was a deeper rupture at the heart of our democracy than a lot of people realized," said the Rev. Jennifer Bailey, founder and executive director of the Faith Matters Network, which organized the project along with two other nonprofit groups, Hollaback and The Dinner Party.

"One of the best and most ancient practices that have brought people together for millennia is this notion of breaking bread together," Bailey said. So organizers decide to host 100 dinner parties across the country during the first 100 days of Trump's presidency. Some of the gatherings would be focused on groups that feel marginalized by the new administration, Bailey said, but others would aim to create conversation "across lines of difference, whether that's racial, political, ideological, to try to humanize ourselves again." More than 600 people have attended so far.

- - -

When Gabriela Schneider first heard about the project, "I thought - yes, that is what I needed," she told her fellow guests in Sims' dining room. "I want to find people who want to find a way to come together. Because it feels like we are at war."

She paused, and smiled. "Sorry to go all zero-to-60."

Vipin Thekk, a 36-year-old native of India, said he came because "I was hoping to get to understand perspectives other than mine." The election made him realize "how much of a bubble I was in," and he wanted to know more about the people who voted for Trump.

But a dinner party isn't always the most natural way to burst a bubble.

Most of the people who have participated in "100 Days" have been left-leaning, organizers say. And among the group at Sims' home, only one was a Trump voter - and she kept this fact to herself, listening quietly as the others around her spoke first.

A dinner party isn't always the most natural way to burst a bubble

Crystal Yan, a 24-year-old Web designer, said she felt vulnerable when she was harassed by strange men on the street. This drew some words of dismay from Brian Hill, a bearded millennial and the lone white man at the dinner, who was saddened that she had been hassled in his own neighborhood of Mount Pleasant.

Susumu Noda, 27, a software engineer from Tokyo, said he feels self-conscious when conversations turn to politics, which he doesn't follow as closely as other Washingtonians. Sims, who is black, recalled moving back to D.C. after several years away and being stunned by the sweep of gentrification. She found herself intrigued by one new shop, but "I didn't feel comfortable going there, because everyone in line was white."

This drew the attention of Thekk. He wondered: How frequently did this kind of thing happen? "I still don't understand the complexities of race in this country," he said.

Sims said she has a "heightened radar," having watched her family deal with discrimination in her younger days: "I go places and I look around and I think, 'Is there anyone like me here?' "

But where did Somer Salomon feel vulnerable? Right here, she said - at this dinner.

"I guess," she acknowledged, resting her fork against her plate, "I'm the only person who is conservative."

The 42-year-old doctoral candidate told her fellow diners she seems to fall outside the "acceptable range of views" for Washington. "The collective feeling is that to hold different views is either uneducated, or regressive, or it comes from a place of anger - that it can't be a legitimate, thoughtful or educated difference of opinion," she said. "I feel like it's like that more and more - that there is a narrowing of what is acceptable to express."

The room fell silent for a second, save for the soft jazz percolating from the stereo speakers and a glug of wine being poured.

"Thank you for sharing that," Callejon said.

Salomon's disclosure seemed to energize the room. Schneider described how out of place she can feel within her own political tribe - particularly within the "call-out culture" of social media, she said, where people are quick to condemn anyone who disagrees with them.

"I see this a lot on my Facebook," she said. "I'm anti-PC, and I'm probably to the left of Bernie Sanders, but in that way I'm conservative, too."

Salomon nodded. "I find it very counterproductive, this idea that we can just shame people into believing the right thing."

Yan added that she's frustrated by the way too many people conduct political discussions these days, as if the object were to "win" rather than share ideas or build understanding.

"I think we are afraid to let people know when we think they've made a good point or when they might have changed our mind," she said.

Salomon agreed: "A lot of people subscribe to the idea that 'my political beliefs make me a good person.' An older way of thinking would say that what makes you a good person is your actions."

But in these unsettling times, many people are starting to take action, Callejon argued, citing "the Women's March, and people rushing to airports to help immigrants, and Black Lives Matter. People are frickin' scared. This feels really palpable to me."

Some guests nodded, others didn't; there was the vague feeling that some might have thoughts they didn't care to share. So it went through dinner - no raised voices or interruptions, and plenty of thoughtful questions, but very little treading on contentious territory.

When Callejon suggested they serve dessert because it was already 9 o'clock, everyone seemed stunned by how the evening had flown by and hailed it as a success: "I'll carry the memory that this was worthwhile," Noda said.

"I'm just really grateful that everyone was open to coming and having the conversation," Sims said. "People showed up, and that gives me hope."

Around the table, her guests raised their glasses.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world