A new era has begun of "global water bankruptcy", with humans depleting freshwater systems to the point they can't recover, according to a new United Nations report.

Three-quarters of the world's population – about 6.1 billion people – now live in countries where freshwater supplies are insecure or critically insecure, according to the report published Tuesday by UN University's Institute for Water, Environment and Health. Four billion people face severe water scarcity for at least one month a year.

Cities are experiencing more Day Zero events in which municipal water systems near collapse. An acute water shortage in Tehran recently led Iran's president to warn it may become necessary to evacuate parts of the city or even relocate the capital. In Turkey, roughly 700 sinkholes – some up to 100 feet deep – have appeared where aquifers have collapsed after their groundwater was drained.

Drought and water scarcity are likely to drive migrations in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America, says the report, which is based on a peer-reviewed paper.

Global warming is increasing water demands and makes the natural supply of water less predictable. But water management is also a key part of the equation, said Kaveh Madani, director of the UN institute and the lead author of the report. "Water bankruptcy is not about how much water you have; it's about how you manage your water," he said.

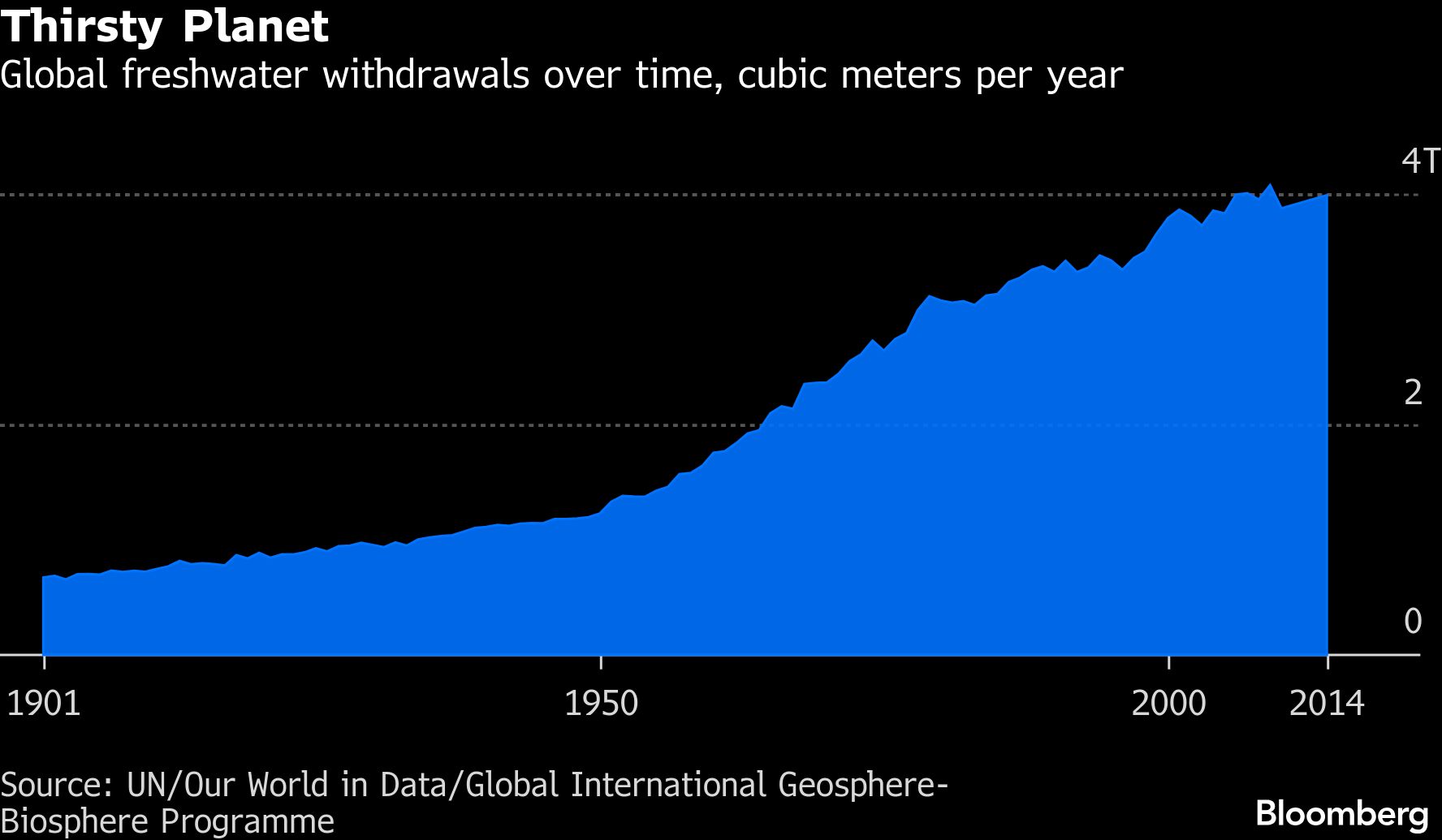

Chronic overuse of groundwater, forest destruction, land degradation and pollution have caused irreversible freshwater loss in many parts of the world – problems that are compounded by climate change.

Climate change is shifting freshwater on a planetary scale and, on a smaller scale, those effects can be made worse by local actions. A hotter, drier planet experiences more water-evaporating droughts. That concentrates salts in the soil, as so do certain farming practices. Higher temperatures contribute to more forest and peatland fires, while human clear-cutting and draining of wetlands worsen fire conditions.

"Droughts are no longer just natural but anthropogenic – meaning that we have climate change at the global level, and then also the land use changes from management decisions and infrastructure allocation decisions make water less and less available," Madani said.

Use of the word "bankruptcy" to describe the extent of water depletion is new for the UN. Previously, UN University scientists used "water stress" or "water crisis" to describe systems that were under either prolonged or sudden and acute pressure. Both of those terms allow for the possibility of recovery.

But that isn't feasible in many areas where humans have overdrawn the local supply of fresh water, squandering the annual influx from recharging sources like rivers and melting snow while exhausting groundwater and other natural reservoirs.

Half the world gets its domestic water from stored groundwater, which is being heavily depleted. But those reliant on water above the surface are also vulnerable. A quarter of the population depends on large lakes that have lost half their water since the early 1990s.

The amount of water available to communities is also often overstated because its quality may be too poor for use, the report says. Fertilisers, mining effluents, plastics and drug contaminants continue to find their way into rivers, lakes and coastal waters around the world, and wastewater treatment practices are often inadequate.

The report calls for the recognition of water bankruptcy in policy debates and for the creation of a global monitoring framework to track water resources. Governments should consider blocking projects that further degrade water supplies, it says.

"Even in years that are wet, we are still struggling," Madani said. "A lot of these systems have been damaged permanently."

Another paper published this month, in Nature, predicted that crop droughts will worsen in much of Europe, northern South America and western North America even as big rain events increase. That's because rising temperatures more strongly affect evaporation and loss of soil moisture in those regions, which means more water will be required for irrigation.

In the tropics, semi-arid areas are more affected by precipitation than by temperature-driven evaporation. On the other hand, they may also experience more extreme heat, which makes plants thirstier, or extreme rainfall that erodes soil.

"Even if, in agriculture, you're not being affected by more of these very dramatic seasonal droughts, you still are affected by increases in extreme weather," said Emily Black, a professor of terrestrial processes and climate at the University of Reading and lead author of the Nature study. "Agriculture is a big user of water, so if we are increasing the water demand from plants, then that of course strains the water supply wherever you are."

The UN report's release comes ahead of meetings in Dakar, Senegal, later this month to lay groundwork for the 2026 UN Water Conference in December. On Jan. 7 the US said it would withdraw from UN Water and UN Universities, along with dozens of other international organisations that the Trump administration said are "contrary to the interests" of the country. The US decision has not impacted operations so far, Madani said, though he added that the country's absence will be felt in Dakar.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world