Elijah "Nature Boy " Alexander chats with Maria Hegstad and her daughter Paisley, 2, in Lafayette Park.

Washington:

Nature Boy was four blocks shy of Lafayette Square when a gray-haired man once among the country's most powerful people stepped onto the 16th Street sidewalk in front of him.

For several seconds, Donald Rumsfeld gazed at Elijah Alfred Alexander Jr., known as Nature Boy since he stopped wearing shoes in 1981, then shirts in 1984. Ivory dreadlocks dangled to his waist, and all that covered his 6-foot-1 frame were a slit pair of jean shorts that resembled a denim loincloth.

The former defense secretary betrayed no surprise - or interest - at the canvas of bare skin on display at 8 a.m. on a 61-degree October weekday. Rumsfeld, 83, crossed the road and disappeared into a downtown D.C. office building.

Alexander, who seconds earlier had stopped to urinate between two evergreens, was equally unmoved. "Boy, he's aged," said the 70-year-old, sporting a look sometimes compared to Methuselah's.

Crossing paths with an architect of the Afghanistan and Iraq invasions didn't feel special, because, for Alexander, it's not.

The Vietnam veteran spends most days in the historic, tree-shaded square across from the White House. "My office," as Alexander calls the seven-acre park, draws visitors from around the world, along with legions of lawyers, lobbyists and administration officials headed for work.

Alexander - who has a tiny apartment, 5,000 Facebook friends and an unexpected rapport with the Secret Service - revels in his role as one of the District's most visible eccentrics. In a city of heels and wing tips, suit jackets and cellphones, government badges and top-level security clearances, he has become a cherished fixture for federal workers, a tour stop for sightseeing groups and a giggle-inducing curiosity for flocks of schoolchildren.

Almost none of them know about the long, delusion-riddled journey that brought him to the nation's capital six years ago. Or about his declared political intentions - to become the country's next president before civilization ends in 2028. But their opinions of him probably wouldn't change much even if they did.

He is a prophet of doom who wields a five-toothed smile instead of a megaphone. He is a source of momentary encouragement to some and a guru of perpetual wisdom to others - all while sitting nearly naked outside the home of the free world's leader.

Beneath the statue of Andrew Jackson's rearing horse, Alexander sat on a park bench in the center of Lafayette Square and carefully removed the thick rubber band that held shut a weathered, cream-colored glasses case. He slipped on his $5 spectacles and twisted out the lead from a yellow Paper Mate mechanical pencil.

Alexander then turned to Page 25 of The Washington Post Express and embarked on his morning's most strenuous challenge: the Sudoku puzzle.

Dress shoes clicked across the red bricks in front of him.

"Morning," said a fast-walking woman in tan pants and tennis shoes, her federal identification hanging from a lanyard. "How are you?"

"I'm well, thank you," he responded, looking up. "Enjoy your day."

"One of my regulars," he added.

A Secret Service agent, head shaved and pistol holstered, soon approached.

"Morning, Elijah," the man said.

"Morning," he said back. "Enjoy your day."

He has delivered that message - enjoy your day - thousands of times here. Although he has never experienced it himself, Alexander recognizes the pressures of District work life and lends to those wearied by it his unorthodox brand of optimism.

"There's something special about him," said Bryan Vidal, a 29-year-old government contractor who works nearby and considers Alexander his closest friend. "He's like the only person that I can totally be a genuine human being around."

Washington has always attracted peculiar people with political causes, including the Florida mailman who landed a gyrocopter on the Capitol lawn in April to demand campaign-finance reform and "Tractor Man," who drove his John Deere into a pond on the Mall in 2003 to defend tobacco farmers. Nature Boy has an agenda, too; he just preaches it much more quietly.

As the sun climbed, more tourists streamed into the park, and a familiar routine began.

Three young men walked by him, glanced, grinned, whispered, then glanced again. Eventually, one came over.

"Hello, sir," he said, his accent thick.

"Don't call me 'sir,' " Alexander said, extending his hand. "Call me 'brother.' "

"Photo take?" the teen asked, and within minutes, 10 Turkish college students, then in the United States fewer than 24 hours, gathered around him to snap selfies and collect advice on where to meet women.

A bit later, Alexander peered toward the White House and eyed a bobbing umbrella covered in colorful fish. He smiled. Beneath it was German-born Inge Schmidt, one of his favorite tour guides.

But just as she turned in his direction, the Secret Service began to clear the park for a brief closure. Frustrated, Alexander headed north, where along the sidewalk she spotted him.

"There you are!" Schmidt yelled.

And then, as always, she extended her hand, and he bowed his head to kiss it. Her stunned sightseers shot pictures that would inevitably land on social media.

"He's probably as well known in Germany," she said later, "as he is in this country."

Alexander understands his viral appeal. For a man who has devoted 39 years to a oneness with nature, he has made remarkably good use of the Internet.

"Check out my website," he often tells people about the page he manages with his single possession of real value: a $1,500 MacBook.

His Facebook profile features dozens of images of him posing with admirers and even more posts castigating the government. A "Lover of Wisdom," he wrote in the "Details About Elijah" section, predicting that he will survive civilization's end. "So I'm seeking others to survive with me."

Alexander's online presence has made him more approachable for many people, including Wendy Young, who finally mustered the courage that afternoon to request the photo she had wanted for years.

"C'mon," Alexander said, beaming. "Get in my arms, girl."

They sat on a bench, and he pulled Young into him as her friend took pictures.

"How are you doing, Wendy?" he asked, mid-photo shoot.

"I'm good," said Young, a researcher for North America's Building Trades Unions on 16th Street NW. "How are you?"

"I've got Wendy in my arms," he bellowed, expelling a deep, gritty laugh that punctuates most of his conversations. "I'm doing great."

As Young told him how carefree he seemed, Alexander extended his feet, stretched his arms wide and smiled.

"I'm the freest man in America."

He wasn't always.

Raised on a farm in Louisiana, he can still recall walking shoeless atop the plowed soil and stepping in the footprints of a father who would soon abandon him.

At age 8, he moved with his mother and four siblings to Fort Worth to live near an uncle. Young Elijah was smart and eventually finished high school, but he questioned everyone and everything.

"Headstrong and defiant," said his sister, Annie McDaniel, 75. "He was going to do what he wanted to do."

Alexander insists that a voice in his mind - "the spirit" - first spoke to him as he wailed in a crib as an infant, delivering a message he has embraced ever since: "You may as well be content. No one is coming to get you."

Alexander went on to serve two tours in Vietnam as a plane mechanic for the Air Force. He is twice divorced and has six children, he believes, with five different women. He has never met two of the kids. One - his namesake - played linebacker for four NFL teams over a decade before dying in 2010 after a battle with cancer. Alexander had no relationship with him and didn't attend the funeral.

He speaks regularly to only one of his children, his oldest son, James Washington, a 50-year-old hotel clerk in Texas.

Even so, Alexander said, "I've got no regrets." He believes that nothing is good or bad, it just is. Destiny determines all.

It was destiny, he said, for him to leave his family, a job at a phone company and $2,000 in debt four decades ago to become "the nomad." By foot or rides hitched, he has since traveled to 44 states, Canada and Central America.

In Belize, he said he spent time in a mental hospital and was injected with antipsychotics. In the United States, he has been arrested dozens of times, mostly related to his attire. He was imprisoned in Louisiana for three years in the early '90s for obscenity, a charge under state law related to public exposure.

Asked about Alexander, Secret Service spokesman Robert Hoback said in an email that the agency couldn't discuss "our interactions with this gentleman," but added: "I would just say that our folks are indeed aware of him."

Before his mother died, she theorized that perhaps someone had drugged Alexander and that what he had become was not his fault.

"Mother was just regretful," said his brother, Frank, a 72-year-old Baptist preacher, "that such a gifted person would take that route."

Alexander shook his head, annoyed. Through a loudspeaker, a woman near the White House shouted about war.

Most protesters baffle him. Why complain, he often asks, without suggesting a solution?

Alexander doesn't hesitate to complain because, with a perspective that's part-preposterous and part-profound, he has a suggested solution for almost everything.

He treats the flu with corn whiskey and cuts on his feet with packed dirt. He maintains his health with soap-free, bimonthly baths and a coat of vitamin E oil. ("I shine like new money.") He never allows his heater above 65 degrees in the winter so that he can remain acclimated, and, even in frigid temperatures, he refuses to wear sandals or a shirt unless he's entering a business.

Then there are his bigger ideas.

He is a 9/11-conspiracy theorist and insists that all involved in the attacks and coverup should be imprisoned, including President Barack Obama, who Alexander believes he will soon be asked to replace.

He didn't foresee such a grandiose future when he first moved to the District in 2009, after the death of his longtime friend, William Thomas Hallenback Jr., who founded the famed White House peace vigil. Concepcion Picciotto, who joined the protest in 1981 and has led it for years, barred Alexander from involvement, recently describing him as "disgusting."

He bounced around, and for a few months he was homeless, until 2012 when friends helped him collect Social Security. He eventually moved into his subsidized Columbia Heights apartment, where out of his $900 in monthly income, he pays $125 in rent for an efficiency the size of a one-car garage.

Just after 3 p.m., he slipped on his backpack and headed up 16th Street NW toward home, striding with a hitch in his right knee and a droop in his left shoulder.

He passed the Jefferson Hotel, where rooms go for $700 a night. A doorman in a crisp, dark suit yelled: "I checked out the website. It's good."

As he crossed into Scott Circle Park, a bicyclist zipped by and shouted a greeting.

Alexander continued on for two miles, veering into the grass when possible to preserve his toes, which resemble freshly unearthed tree roots. He lurched up four flights of stairs to the apartment. He sat on his sofa bed, propped atop a collection of dairy crates, and opened a red folder. He picked up his cellphone and called a number.

"This is Elijah," he said, politely explaining to a woman in the U.S. Attorney General's office that he had mailed an order demanding Obama's impeachment but hadn't received confirmation of its arrival.

The woman, Alexander said, promised she'd get back to him.

For several seconds, Donald Rumsfeld gazed at Elijah Alfred Alexander Jr., known as Nature Boy since he stopped wearing shoes in 1981, then shirts in 1984. Ivory dreadlocks dangled to his waist, and all that covered his 6-foot-1 frame were a slit pair of jean shorts that resembled a denim loincloth.

The former defense secretary betrayed no surprise - or interest - at the canvas of bare skin on display at 8 a.m. on a 61-degree October weekday. Rumsfeld, 83, crossed the road and disappeared into a downtown D.C. office building.

Alexander, who seconds earlier had stopped to urinate between two evergreens, was equally unmoved. "Boy, he's aged," said the 70-year-old, sporting a look sometimes compared to Methuselah's.

Crossing paths with an architect of the Afghanistan and Iraq invasions didn't feel special, because, for Alexander, it's not.

The Vietnam veteran spends most days in the historic, tree-shaded square across from the White House. "My office," as Alexander calls the seven-acre park, draws visitors from around the world, along with legions of lawyers, lobbyists and administration officials headed for work.

Alexander - who has a tiny apartment, 5,000 Facebook friends and an unexpected rapport with the Secret Service - revels in his role as one of the District's most visible eccentrics. In a city of heels and wing tips, suit jackets and cellphones, government badges and top-level security clearances, he has become a cherished fixture for federal workers, a tour stop for sightseeing groups and a giggle-inducing curiosity for flocks of schoolchildren.

Almost none of them know about the long, delusion-riddled journey that brought him to the nation's capital six years ago. Or about his declared political intentions - to become the country's next president before civilization ends in 2028. But their opinions of him probably wouldn't change much even if they did.

He is a prophet of doom who wields a five-toothed smile instead of a megaphone. He is a source of momentary encouragement to some and a guru of perpetual wisdom to others - all while sitting nearly naked outside the home of the free world's leader.

Beneath the statue of Andrew Jackson's rearing horse, Alexander sat on a park bench in the center of Lafayette Square and carefully removed the thick rubber band that held shut a weathered, cream-colored glasses case. He slipped on his $5 spectacles and twisted out the lead from a yellow Paper Mate mechanical pencil.

Alexander then turned to Page 25 of The Washington Post Express and embarked on his morning's most strenuous challenge: the Sudoku puzzle.

Dress shoes clicked across the red bricks in front of him.

"Morning," said a fast-walking woman in tan pants and tennis shoes, her federal identification hanging from a lanyard. "How are you?"

"I'm well, thank you," he responded, looking up. "Enjoy your day."

"One of my regulars," he added.

A Secret Service agent, head shaved and pistol holstered, soon approached.

"Morning, Elijah," the man said.

"Morning," he said back. "Enjoy your day."

He has delivered that message - enjoy your day - thousands of times here. Although he has never experienced it himself, Alexander recognizes the pressures of District work life and lends to those wearied by it his unorthodox brand of optimism.

"There's something special about him," said Bryan Vidal, a 29-year-old government contractor who works nearby and considers Alexander his closest friend. "He's like the only person that I can totally be a genuine human being around."

Washington has always attracted peculiar people with political causes, including the Florida mailman who landed a gyrocopter on the Capitol lawn in April to demand campaign-finance reform and "Tractor Man," who drove his John Deere into a pond on the Mall in 2003 to defend tobacco farmers. Nature Boy has an agenda, too; he just preaches it much more quietly.

As the sun climbed, more tourists streamed into the park, and a familiar routine began.

Three young men walked by him, glanced, grinned, whispered, then glanced again. Eventually, one came over.

"Hello, sir," he said, his accent thick.

"Don't call me 'sir,' " Alexander said, extending his hand. "Call me 'brother.' "

"Photo take?" the teen asked, and within minutes, 10 Turkish college students, then in the United States fewer than 24 hours, gathered around him to snap selfies and collect advice on where to meet women.

A bit later, Alexander peered toward the White House and eyed a bobbing umbrella covered in colorful fish. He smiled. Beneath it was German-born Inge Schmidt, one of his favorite tour guides.

But just as she turned in his direction, the Secret Service began to clear the park for a brief closure. Frustrated, Alexander headed north, where along the sidewalk she spotted him.

"There you are!" Schmidt yelled.

And then, as always, she extended her hand, and he bowed his head to kiss it. Her stunned sightseers shot pictures that would inevitably land on social media.

"He's probably as well known in Germany," she said later, "as he is in this country."

Alexander understands his viral appeal. For a man who has devoted 39 years to a oneness with nature, he has made remarkably good use of the Internet.

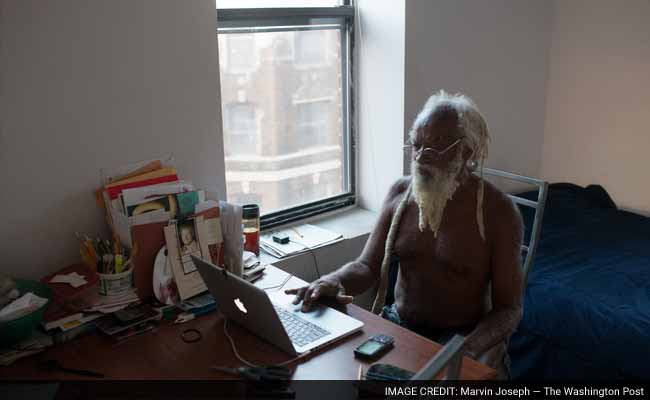

"Check out my website," he often tells people about the page he manages with his single possession of real value: a $1,500 MacBook.

Elijah Alexander chats with many of his Facebook friends on his laptop.

His Facebook profile features dozens of images of him posing with admirers and even more posts castigating the government. A "Lover of Wisdom," he wrote in the "Details About Elijah" section, predicting that he will survive civilization's end. "So I'm seeking others to survive with me."

Alexander's online presence has made him more approachable for many people, including Wendy Young, who finally mustered the courage that afternoon to request the photo she had wanted for years.

"C'mon," Alexander said, beaming. "Get in my arms, girl."

They sat on a bench, and he pulled Young into him as her friend took pictures.

"How are you doing, Wendy?" he asked, mid-photo shoot.

"I'm good," said Young, a researcher for North America's Building Trades Unions on 16th Street NW. "How are you?"

"I've got Wendy in my arms," he bellowed, expelling a deep, gritty laugh that punctuates most of his conversations. "I'm doing great."

As Young told him how carefree he seemed, Alexander extended his feet, stretched his arms wide and smiled.

"I'm the freest man in America."

He wasn't always.

Raised on a farm in Louisiana, he can still recall walking shoeless atop the plowed soil and stepping in the footprints of a father who would soon abandon him.

At age 8, he moved with his mother and four siblings to Fort Worth to live near an uncle. Young Elijah was smart and eventually finished high school, but he questioned everyone and everything.

"Headstrong and defiant," said his sister, Annie McDaniel, 75. "He was going to do what he wanted to do."

Alexander insists that a voice in his mind - "the spirit" - first spoke to him as he wailed in a crib as an infant, delivering a message he has embraced ever since: "You may as well be content. No one is coming to get you."

Alexander went on to serve two tours in Vietnam as a plane mechanic for the Air Force. He is twice divorced and has six children, he believes, with five different women. He has never met two of the kids. One - his namesake - played linebacker for four NFL teams over a decade before dying in 2010 after a battle with cancer. Alexander had no relationship with him and didn't attend the funeral.

He speaks regularly to only one of his children, his oldest son, James Washington, a 50-year-old hotel clerk in Texas.

Even so, Alexander said, "I've got no regrets." He believes that nothing is good or bad, it just is. Destiny determines all.

It was destiny, he said, for him to leave his family, a job at a phone company and $2,000 in debt four decades ago to become "the nomad." By foot or rides hitched, he has since traveled to 44 states, Canada and Central America.

In Belize, he said he spent time in a mental hospital and was injected with antipsychotics. In the United States, he has been arrested dozens of times, mostly related to his attire. He was imprisoned in Louisiana for three years in the early '90s for obscenity, a charge under state law related to public exposure.

Asked about Alexander, Secret Service spokesman Robert Hoback said in an email that the agency couldn't discuss "our interactions with this gentleman," but added: "I would just say that our folks are indeed aware of him."

Before his mother died, she theorized that perhaps someone had drugged Alexander and that what he had become was not his fault.

"Mother was just regretful," said his brother, Frank, a 72-year-old Baptist preacher, "that such a gifted person would take that route."

Alexander shook his head, annoyed. Through a loudspeaker, a woman near the White House shouted about war.

Most protesters baffle him. Why complain, he often asks, without suggesting a solution?

Alexander doesn't hesitate to complain because, with a perspective that's part-preposterous and part-profound, he has a suggested solution for almost everything.

He treats the flu with corn whiskey and cuts on his feet with packed dirt. He maintains his health with soap-free, bimonthly baths and a coat of vitamin E oil. ("I shine like new money.") He never allows his heater above 65 degrees in the winter so that he can remain acclimated, and, even in frigid temperatures, he refuses to wear sandals or a shirt unless he's entering a business.

Then there are his bigger ideas.

He is a 9/11-conspiracy theorist and insists that all involved in the attacks and coverup should be imprisoned, including President Barack Obama, who Alexander believes he will soon be asked to replace.

He didn't foresee such a grandiose future when he first moved to the District in 2009, after the death of his longtime friend, William Thomas Hallenback Jr., who founded the famed White House peace vigil. Concepcion Picciotto, who joined the protest in 1981 and has led it for years, barred Alexander from involvement, recently describing him as "disgusting."

He bounced around, and for a few months he was homeless, until 2012 when friends helped him collect Social Security. He eventually moved into his subsidized Columbia Heights apartment, where out of his $900 in monthly income, he pays $125 in rent for an efficiency the size of a one-car garage.

Just after 3 p.m., he slipped on his backpack and headed up 16th Street NW toward home, striding with a hitch in his right knee and a droop in his left shoulder.

He passed the Jefferson Hotel, where rooms go for $700 a night. A doorman in a crisp, dark suit yelled: "I checked out the website. It's good."

As he crossed into Scott Circle Park, a bicyclist zipped by and shouted a greeting.

Alexander continued on for two miles, veering into the grass when possible to preserve his toes, which resemble freshly unearthed tree roots. He lurched up four flights of stairs to the apartment. He sat on his sofa bed, propped atop a collection of dairy crates, and opened a red folder. He picked up his cellphone and called a number.

"This is Elijah," he said, politely explaining to a woman in the U.S. Attorney General's office that he had mailed an order demanding Obama's impeachment but hadn't received confirmation of its arrival.

The woman, Alexander said, promised she'd get back to him.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world