New Delhi:

Hundreds of reporters stood waiting, everyone expecting a helping of scandal, and Arvind Kejriwal did not disappoint. He pushed past the television cameras, smiling slyly in his white Gandhian cap, and took a seat on the podium. The crowd pressed forward, drawn by the question now shaking India's political establishment: Who will Arvind go after next?

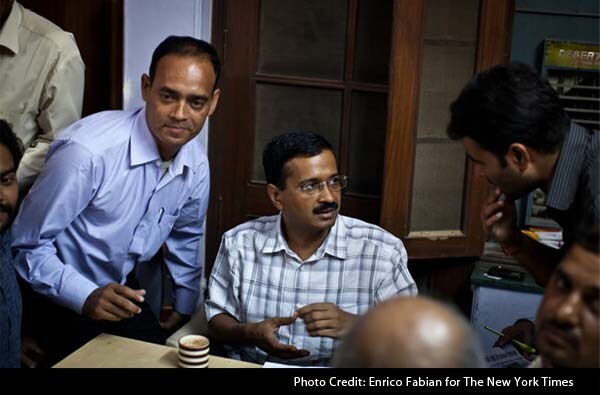

Slight and bespectacled, with a neatly trimmed mustache, Mr. Kejriwal, 44, could be mistaken for a bookkeeper, rather than what he has become - the unlikely bomb thrower of Indian politics. His recent appearance was one of his staged media spectacles, in which he has produced documents and levelled corruption charges at some of India's most powerful political figures. Corruption, he argues, corrodes all the political parties in a fundamentally compromised system.

His solution? The formation of a new political party, in time for national elections in 2014.

"We hope that the people of this country will be able to do something in 2014," Mr. Kejriwal said.

That Mr. Kejriwal is now one of India's most powerful figures represents a strikingly swift turnaround. Only months ago, conventional wisdom held that he was finished politically. He had been the mastermind of the huge anticorruption movement that last year shook the country - but had then seemed to miscalculate.

First, the movement fizzled. Then, earlier this year, his alliance shattered with Anna Hazare, the hunger striker and symbol of the movement: Mr. Hazare unexpectedly balked over plans to form a political party.

Politicos snickered that Mr. Kejriwal's party, without Mr. Hazare, would be dead before it was born. Mr. Kejriwal, the backstage manager, would now be the public face, which raised a question: Would ordinary Indians rally behind a party whose public draw was a wiry, intense former tax examiner? That remains to be seen, but no one is snickering at Mr. Kejriwal any longer.

Instead, he is feared. He has accused Robert Vadra, the son-in-law of Sonia Gandhi, the country's most powerful politician, of reaping millions in improper real estate deals. He has delved into the business dealings of Nitin Gadkari, leader of the main opposition party. He has alleged improprieties in a charity for the handicapped run by the family of Salman Khurshid, the country's new foreign minister - prompting a barely veiled threat from Mr. Khurshid.

In some instances, he is merely resurrecting and amplifying existing accusations. Yet, through it all, Mr. Kejriwal has steadily pushed his simple, if radical, message: India's democracy, the largest in the world, does not merely need reform. India needs a revolution.

It is Sunday night, three days after Mr. Kejriwal's news conference on Oct. 25. His target that day was Reliance Industries Ltd., India's most powerful corporation, which he accused of exerting political influence to bilk billions of dollars on natural gas contracts. (On Friday, Mr. Kejriwal held another news conference, this time accusing Mukesh Ambani, the owner of Reliance, and others of illegally stashing money overseas.)

Reliance has denied the charges - as have all of his targets - but Mr. Kejriwal seemed pleased. The establishment has been rattled.

Now Mr. Kejriwal sat inside a cramped conference room of his headquarters, in a small house at the edge of the capital, beside a dingy slum. He was engaged in a ritual of Indian politics: the public audience. One man had travelled hundreds of miles to pledge his support. Another unexpectedly started singing a tribute song. A father and mother presented their 10-year-old son as a future foot soldier in Mr. Kejriwal's efforts.

"After seeing you," the boy's mother said, "I have the courage that now we can raise our voices."

Mr. Kejriwal grew up in the city of Hisar, in the northern state of Haryana, the son of an engineer. Like many ambitious Indians, his parents wanted him to become a doctor or an engineer, and the young Mr. Kejriwal studied obsessively to gain entrance to India's most prestigious engineering school. After graduation, he worked for three years as a mechanical engineer before testing into India's elite civil service as a tax examiner.

It would change his life. He met his wife, another tax examiner, but also found himself confronted with rampant bribe-taking. "There was corruption at every stage," Mr. Kejriwal recalled.

He grew disillusioned and quietly got involved in the nationwide effort by civil society groups that resulted in the Right to Information, the 2005 law that established a public right to access official records and documents. He had taken a formal leave from the tax bureau in 2000 and would earn international recognition after founding Parivartan, a nonprofit group focused on government transparency and accountability.

Then in 2006, Mr. Kejriwal decided to quit the civil service to become a full-time social activist, tendering his resignation without even telling his wife. Four years later, Mr. Kejriwal became involved in efforts that have lasted for decades to create an independent anticorruption agency, known as the Lokpal.

The Lokpal campaign, led by Mr. Hazare, brought together an odd coalition of civil society leaders, in what became known as Team Anna. To a degree, Mr. Kejriwal was the least established of these advisers, yet he quickly positioned himself as the key adviser to Mr. Hazare. And he was instrumental in building an organization, India Against Corruption, that was laden with technology-savvy young people who used the Internet and social media to make the Lokpal cause a nationwide campaign.

But if some allies regarded Mr. Kejriwal as a committed activist and brilliant tactician, others saw him as calculating and manipulative, a Rasputin whispering in Mr. Hazare's ear.

"I could see through Arvind's manipulative tactics from the very beginning," said Swami Agnivesh, a longtime social activist who broke from Team Anna. "He was trying to get control of Anna, more and more."

Ultimately, Team Anna splintered, after efforts stalled to pass Lokpal legislation in India's Parliament. Today, Mr. Kejriwal blames India's lawmakers for breaking their promise; yet others say Mr. Kejriwal's uncompromising nature and refusal to budge in negotiations helped kill any deal.

"Today," Mr. Kejriwal said, "these parties are very good at fighting elections on the basis of money and muscle power. We cannot win on that turf."

The question, of course, is whether Mr. Kejriwal's party can win anything at all. He and his team are expected to announce formal plans for the party - as well as the party's name - at some point this month. Mr. Kejriwal has certainly tapped into public anger over official corruption, especially among India's urban middle class, yet there is no certainty that anger will translate into votes against established parties with entrenched vote bank machines.

Mr. Kejriwal also has competition on other fronts: Mr. Hazare and a handful of others are reconstituting their anticorruption movement, even contemplating opening an office down the street from Mr. Kejriwal, according to Indian news media. But Mr. Kejriwal is careful to praise Mr. Hazare, saying he remains an ally, while emphasizing that the decision to enter electoral politics was a difficult one.

"We are getting into the system to change the system," he said.

Mr. Kejriwal said his initial focus would be to field candidates in next year's state elections in Delhi, the city-state that includes the national capital, New Delhi. This might be his best chance, since much of the middle class uprising over the Lokpal occurred in the capital. Meanwhile, Mr. Kejriwal seems likely to keep attacking the political elite.

"This little tiny ant has gotten inside the trunk of an elephant," said Yogendra Yadav, a prominent political scientist who is serving as an adviser to the new party, "and the elephant is hopping mad."

Hari Kumar contributed reporting from New Delhi.

Slight and bespectacled, with a neatly trimmed mustache, Mr. Kejriwal, 44, could be mistaken for a bookkeeper, rather than what he has become - the unlikely bomb thrower of Indian politics. His recent appearance was one of his staged media spectacles, in which he has produced documents and levelled corruption charges at some of India's most powerful political figures. Corruption, he argues, corrodes all the political parties in a fundamentally compromised system.

His solution? The formation of a new political party, in time for national elections in 2014.

"We hope that the people of this country will be able to do something in 2014," Mr. Kejriwal said.

That Mr. Kejriwal is now one of India's most powerful figures represents a strikingly swift turnaround. Only months ago, conventional wisdom held that he was finished politically. He had been the mastermind of the huge anticorruption movement that last year shook the country - but had then seemed to miscalculate.

First, the movement fizzled. Then, earlier this year, his alliance shattered with Anna Hazare, the hunger striker and symbol of the movement: Mr. Hazare unexpectedly balked over plans to form a political party.

Politicos snickered that Mr. Kejriwal's party, without Mr. Hazare, would be dead before it was born. Mr. Kejriwal, the backstage manager, would now be the public face, which raised a question: Would ordinary Indians rally behind a party whose public draw was a wiry, intense former tax examiner? That remains to be seen, but no one is snickering at Mr. Kejriwal any longer.

Instead, he is feared. He has accused Robert Vadra, the son-in-law of Sonia Gandhi, the country's most powerful politician, of reaping millions in improper real estate deals. He has delved into the business dealings of Nitin Gadkari, leader of the main opposition party. He has alleged improprieties in a charity for the handicapped run by the family of Salman Khurshid, the country's new foreign minister - prompting a barely veiled threat from Mr. Khurshid.

In some instances, he is merely resurrecting and amplifying existing accusations. Yet, through it all, Mr. Kejriwal has steadily pushed his simple, if radical, message: India's democracy, the largest in the world, does not merely need reform. India needs a revolution.

It is Sunday night, three days after Mr. Kejriwal's news conference on Oct. 25. His target that day was Reliance Industries Ltd., India's most powerful corporation, which he accused of exerting political influence to bilk billions of dollars on natural gas contracts. (On Friday, Mr. Kejriwal held another news conference, this time accusing Mukesh Ambani, the owner of Reliance, and others of illegally stashing money overseas.)

Reliance has denied the charges - as have all of his targets - but Mr. Kejriwal seemed pleased. The establishment has been rattled.

Now Mr. Kejriwal sat inside a cramped conference room of his headquarters, in a small house at the edge of the capital, beside a dingy slum. He was engaged in a ritual of Indian politics: the public audience. One man had travelled hundreds of miles to pledge his support. Another unexpectedly started singing a tribute song. A father and mother presented their 10-year-old son as a future foot soldier in Mr. Kejriwal's efforts.

"After seeing you," the boy's mother said, "I have the courage that now we can raise our voices."

Mr. Kejriwal grew up in the city of Hisar, in the northern state of Haryana, the son of an engineer. Like many ambitious Indians, his parents wanted him to become a doctor or an engineer, and the young Mr. Kejriwal studied obsessively to gain entrance to India's most prestigious engineering school. After graduation, he worked for three years as a mechanical engineer before testing into India's elite civil service as a tax examiner.

It would change his life. He met his wife, another tax examiner, but also found himself confronted with rampant bribe-taking. "There was corruption at every stage," Mr. Kejriwal recalled.

He grew disillusioned and quietly got involved in the nationwide effort by civil society groups that resulted in the Right to Information, the 2005 law that established a public right to access official records and documents. He had taken a formal leave from the tax bureau in 2000 and would earn international recognition after founding Parivartan, a nonprofit group focused on government transparency and accountability.

Then in 2006, Mr. Kejriwal decided to quit the civil service to become a full-time social activist, tendering his resignation without even telling his wife. Four years later, Mr. Kejriwal became involved in efforts that have lasted for decades to create an independent anticorruption agency, known as the Lokpal.

The Lokpal campaign, led by Mr. Hazare, brought together an odd coalition of civil society leaders, in what became known as Team Anna. To a degree, Mr. Kejriwal was the least established of these advisers, yet he quickly positioned himself as the key adviser to Mr. Hazare. And he was instrumental in building an organization, India Against Corruption, that was laden with technology-savvy young people who used the Internet and social media to make the Lokpal cause a nationwide campaign.

But if some allies regarded Mr. Kejriwal as a committed activist and brilliant tactician, others saw him as calculating and manipulative, a Rasputin whispering in Mr. Hazare's ear.

"I could see through Arvind's manipulative tactics from the very beginning," said Swami Agnivesh, a longtime social activist who broke from Team Anna. "He was trying to get control of Anna, more and more."

Ultimately, Team Anna splintered, after efforts stalled to pass Lokpal legislation in India's Parliament. Today, Mr. Kejriwal blames India's lawmakers for breaking their promise; yet others say Mr. Kejriwal's uncompromising nature and refusal to budge in negotiations helped kill any deal.

"Today," Mr. Kejriwal said, "these parties are very good at fighting elections on the basis of money and muscle power. We cannot win on that turf."

The question, of course, is whether Mr. Kejriwal's party can win anything at all. He and his team are expected to announce formal plans for the party - as well as the party's name - at some point this month. Mr. Kejriwal has certainly tapped into public anger over official corruption, especially among India's urban middle class, yet there is no certainty that anger will translate into votes against established parties with entrenched vote bank machines.

Mr. Kejriwal also has competition on other fronts: Mr. Hazare and a handful of others are reconstituting their anticorruption movement, even contemplating opening an office down the street from Mr. Kejriwal, according to Indian news media. But Mr. Kejriwal is careful to praise Mr. Hazare, saying he remains an ally, while emphasizing that the decision to enter electoral politics was a difficult one.

"We are getting into the system to change the system," he said.

Mr. Kejriwal said his initial focus would be to field candidates in next year's state elections in Delhi, the city-state that includes the national capital, New Delhi. This might be his best chance, since much of the middle class uprising over the Lokpal occurred in the capital. Meanwhile, Mr. Kejriwal seems likely to keep attacking the political elite.

"This little tiny ant has gotten inside the trunk of an elephant," said Yogendra Yadav, a prominent political scientist who is serving as an adviser to the new party, "and the elephant is hopping mad."

Hari Kumar contributed reporting from New Delhi.

© 2012, The New York Times News Service

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world