"A little learning is a dang'rous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not of the Pierian spring"

- Alexander Pope

For those who, like me, who would wish to be enlightened as to what is the "Pierian spring", I have looked up Wikipedia on behalf of all of us and there it says, "In Greek mythology, it was believed that drinking from the Pierian spring would bring great knowledge and inspiration". A literary critic, Susan Eiche, has further elaborated (Richmond News, August 27, 2014): "Pope is saying that a little knowledge will only befuddle, misleading us into thinking we know more than in fact we do".

Such rumination on my part is principally in consequence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama having startled me and my ilk by his wholly unwarranted assertion that "I think Mahatma Gandhi-ji was very much willing to give the Prime Ministership to Jinnah. But Pandit Nehru refused. I think it was a little self-centred attitude of Pandit Nehru that he should be Prime Minister. Mahatma Gandhi's thinking, if it had materialized...then India, Pakistan would have been united".

It must be quickly added that within a day, His Holiness graciously withdrew his charge, saying, "I apologize if I said something wrong".

Nevertheless, this faux pas does offer the opportunity to clear the air about the circumstances in which Mahatma Gandhi made the offer of Prime Ministership to Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah and what followed.

Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama said that India and Pakistan would have remained one if Pandit Nehru had accepted Gandhi-ji's choice of Muhammed Ali Jinnah as the country's first PM

On April 1, 1947 (I am deliberately not saying April Fool's Day), Mahatma Gandhi paid a call on the newly arrived Viceroy, Rear Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten of Burma.

Mountbatten recorded that Gandhi-ji opened the discussion by giving the Viceroy a "brief summary of the solution which he asked me to adopt." The solution was that "Mr. Jinnah should forthwith be asked to form the Central Interim Government with Members of the Muslim League". Readers (and His Holiness, if he so wishes) might note that this was not the offer of the Prime Ministership of independent India to Mr. Jinnah, but an invitation to him to head the interim government till Independence was proclaimed (then scheduled for over a year later, by June 1948).

Technicalities aside, Mountbatten recorded that "the solution coming at this time staggered me". Had Mountbatten been better acquainted with our Freedom Struggle than he evidently was, there was no cause for him to be "staggered". For the Mahatma had been repeatedly making this offer to Jinnah since at least 1942. As cited by Stanley Wolpert in his admiring biography of Jinnah, "Jinnah of Pakistan" (OUP, 1984, p. 208), Gandhi wrote to the Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, on August 8, 1942, on the very eve of launching the Quit India movement: "the Congress will have no objection to the British Government transferring all the powers it exercises to the Muslim League on behalf of the whole of India". Gandhi-ji added: "And the Congress will not only not obstruct any Government that the Muslim League may form on behalf of the people, but will even join the Government in running the machinery of the free State." He emphatically concluded: "This is meant in all seriousness and sincerity".

"Staggered" or not, Mountbatten took the precaution of seeking Gandhi's "permission" to "discuss the matter with Pandit Nehru" but "in strict confidence". The Mahatma readily agreed.

The very same afternoon, Nehru met with Mountbatten. Mountbatten recorded: "Pandit Nehru was not surprised to hear of the solution which had been suggested". Indeed, there was no need for any surprise because, as Nehru pointed out to Mountbatten, "this was the same solution that Mr. Gandhi had put up to the Cabinet Mission" (that had visited India in the summer of 1946).

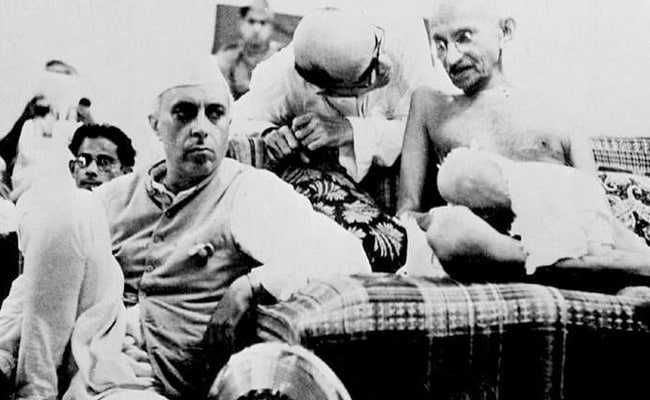

Mahatma Gandhi with Jawaharlal Nehru during a Congress Party meeting (August, 1942)

Indeed, Nehru could have pointed out to His Excellency (which is how Mountbatten loved to be addressed) that since almost the morrow of the Muslim League's Lahore resolution of March 23, 1940, the Congress had been attempting to persuade Jinnah and his League not to press the Pakistan demand as the Congress was more than willing to ensure that, to avoid partition, post-Independence, the reins of power could be passed to the hands of Jinnah and his League. In August 1940, five months after the Lahore resolution, Rajaji floated the balloon through an interview to the Daily Herald saying that "if His Majesty's Government would agree to a Provisional National Government being formed at once, he would persuade his colleagues in the Congress to agree to the Muslim League being invited to nominate the Prime Minister who would form the National Government as he might consider best."

This was followed by a letter from Gandhi-ji to Viceroy Linlithgow saying he was welcome to form a Cabinet "composed of representatives of different parties" and "the Congress would be content to remain in opposition". Obviously, any such non-Congress Cabinet would be headed by a nominee of the Muslim League. Who else but Jinnah?

This shows that neither Gandhi nor the Congress had deviated from the offer made to Jinnah over the long period of two years from 1940 to 1942.

The question of who would lead the government of a united India did not arise during the Jinnah-Gandhi talks of September 1944, which were focused on whether India would remain united or would be vivisected. But, as Nehru noted in his April 1, 1947 conversation with Mountbatten, Gandhi-ji did revive his proposal for a Jinnah-led government to the 1946 Cabinet Mission. The Cabinet Mission, however, "turned down" the suggestion "as being quite impracticable". Nehru had nothing to do with either making the proposal or turning it down.

It was not Nehru but Jinnah who rejected Gandhi-ji's offer. As Wolpert puts it, "Such an offer might have tempted Jinnah if he believed in or trusted Gandhi". He did not. Instead, as he told the press, "Mr. Gandhi's conception of 'Independent India' is basically different from ours", adding, "Mr. Gandhi by independence means Congress raj". Gandhi-ji understood this so well that even in his April 1, 1947 conversation, in reply to Mountbatten's query about what Jinnah would say to such a proposal, Gandhi-ji himself wryly replied, "If you tell him I am the author, he will reply, 'Wily Gandhi' ". Mountbatten, attempting to be equally witty, said, "And I presume Mr. Jinnah would be right?" Pat came Gandhi-ji's reply, "No, I am entirely sincere in my suggestion."

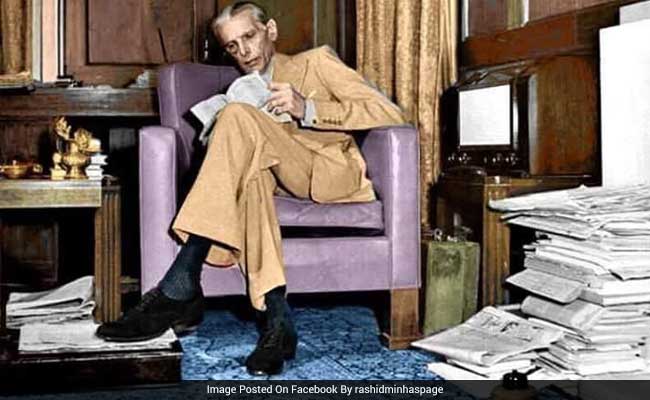

Jinnah became the founding father of Pakistan when the subcontinent was partitioned in 1947 following India's independence from British rule

In this connection, VP Menon, constitutional adviser to the Viceroy, recorded a detailed note that is unfortunately undated but readily available in the Mountbatten Papers. Menon wrote to Mountbatten that Gandhi-ji "knows full well that similar offers have been made to him (Jinnah) in the past as well and that Jinnah never took them seriously". He adds, "No one - least of all the Muslim League - took this offer seriously; the joke, if it was a joke, failed to amuse the Congress world; and it thoroughly annoyed the Hindu Mahasabha". To, therefore, suggest to a new generation of students born decades after these events that Nehru opposed Gandhi-ji's suggestion because he, Nehru, was hungering to become PM is both cruel and unfair and totally unhistorical. It was Jinnah who refused to countenance Gandhi-ji's suggestion.

A staff meeting followed on April 5, 1947. Lord Ismay, chief of staff to the Viceroy, opened by reporting on his one-hour meeting with Gandhi-ji following Gandhi-ji's call on the Viceroy. "The salient features of this scheme," said Ismay, "were that Mr Jinnah be given the option of forming a Cabinet of his own selection; and that if he rejected the offer, the same offer should be made mutatis mutandis to Congress". Ismay went on to stress, "Mr. Gandhi's proposition had already been put up to Mr. Jinnah who had rejected it and would do so again." Of course, Gandhi-ji knew Jinnah would reject the option. But if he did, the way would be opened to Congress forming the Cabinet.

Following the Mountbatten-Gandhi and Mountbatten-Nehru meetings of April 1, the senior staff of the Viceroy, after consultation among themselves, "had come to the unanimous conclusion that Mr. Gandhi's scheme was not workable". The reasons the staff cited for the proposition being unworkable included: "Mr. Jinnah's Government would be completely at the mercy of the Congress majority"; hence, "every single legislative or political measure would be brought up to the Viceroy for decision, and every action the Viceroy took after the initial stages would be misrepresented." Thus, to save the Viceroy's skin, the staff begged him to not pursue this any further. Nehru had nothing to do with any of this.

British Governor-General Lord Mountbatten (centre) and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as they witness the raising of the Indian tricolour for the first time at India Gate in New Delhi (August, 1947)

Mountbatten, however, over-ruled his staff's opinion and insisted that the Gandhi option be included in the panoply of options he proposed placing before Jinnah. Accordingly, on April 6, 1947, Lord Ismay drafted the "Outline of a Scheme for an Interim Government pending Transfer of Power". Readers may please note that this was not a scheme for the exercise of power in an Independent India (with or without Pakistan). The Outline said at point one, "Mr. Jinnah to be given the option of forming a Cabinet"; point two said, "The selection of the Cabinet is left entirely to Mr. Jinnah". The other points need not detain us further for Jinnah rejected the Gandhi option as presented to him by the Viceroy.

On April 7 and 8, 1947, Mountbatten met with Jinnah twice.

While it was Mountbatten's insistence on partitioning Punjab and Bengal that troubled Jinnah most, on the question of his becoming Prime Minister, "Jinnah referred that the Viceroy had said that he (Note: The Viceroy, not Gandhi) wanted him to be Prime Minister, but as he had opposed the Cabinet Mission Plan, the chances were no more of it". By April 10, even Mountbatten gave up, recording, "Mr. Jinnah was a psychopathic case". On April 11, Gandhi-ji wrote to Mountbatten that he wished to be "omit(ted)" from the Viceroy's "consideration". His proposal was thus not pursued further.

Hence, it was not Nehru's aching desire to be PM but principally Jinnah himself, Mountbatten and his staff, the Congress Working Committee and eventually a despairing Gandhi-ji who gave up on this will o' the wisp of keeping India united by making Jinnah PM. That should end such damaging forays into history as, alas, the Dalai Lama allowed himself to make. The nation should be grateful to His Holiness for withdrawing his remark before further damage was caused.

(Mani Shankar Aiyar is former Congress MP, Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.