Blog | Hey Bollywood, What Is It With The 'Bong Babe' Fetish?

Unlike what might be suggested, 'liberalism' is not stuffed in our potatoes, nor is it a virus Bengali women are born with. One is not born but becomes Rani Chatterjee or Madhu Bose.

In the new Netflix film, Aap Jaisa Koi, love is a lesson. Shrirenu Tripathi (R. Madhavan), a middle-aged professor in Jamshedpur, is arranged to be married to Madhu Bose (Fatima Sana Shaikh), a French tutor in Kolkata. The attraction is immediate. Shrirenu, the 42-year-old virgin, had abandoned the idea of being with anyone, let alone someone like the radiant Madhu; he is naturally thrown off when she likes him back. Everything goes well till a roadblock surfaces. The man turns out to be conservative and the woman is not pleased.

In Hindi cinema, difference has been the cornerstone of love. Contrast - behavioural (introvert-extrovert) and social (class and caste) - attracts. It brings people together and emboldens them to fight against others. Love is the bridge where they meet, and the journey to be together supplies the story. The higher the stakes, the greater the love story.

The Veers And Salims Of Bollywood

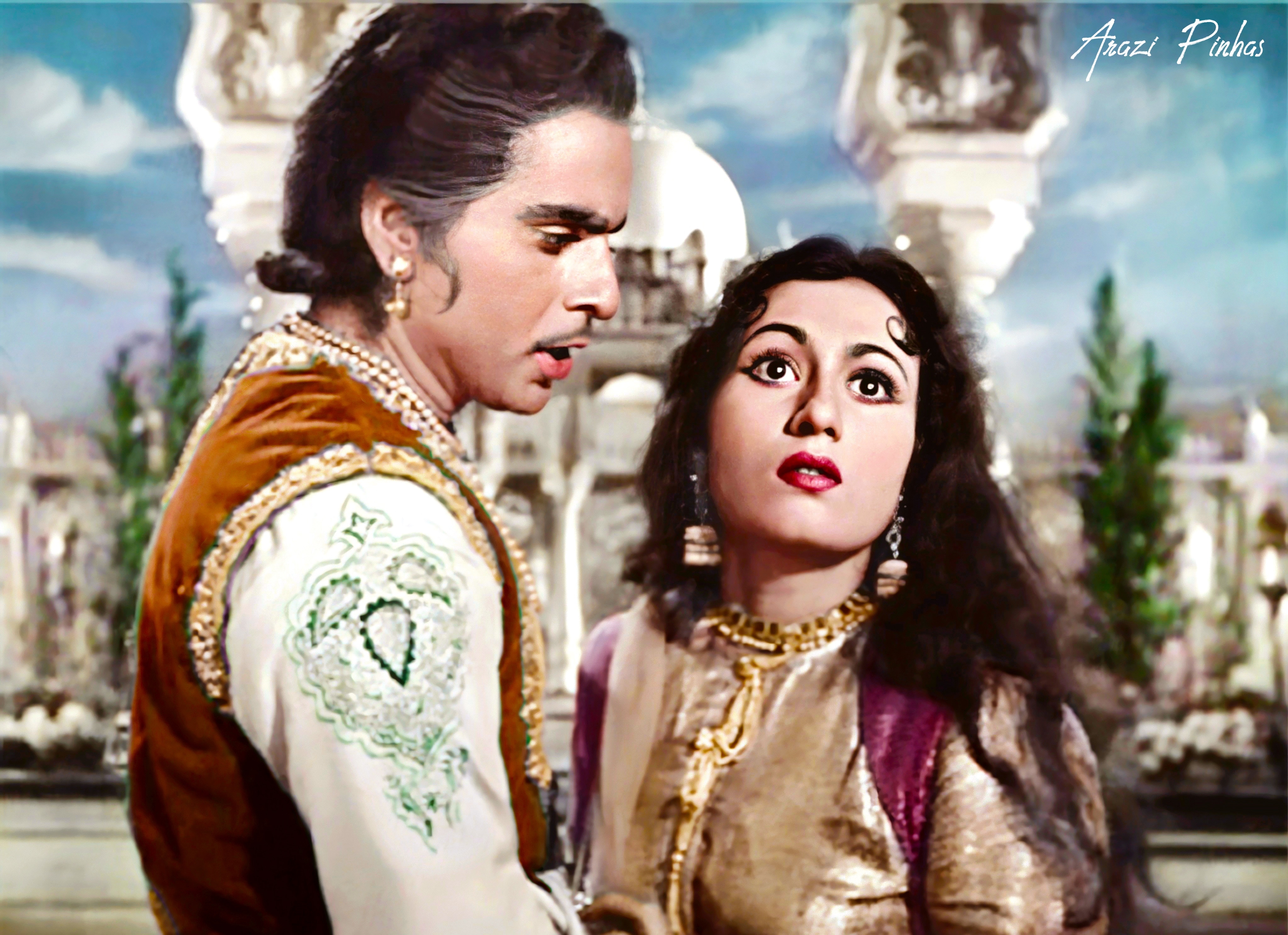

Classic love stories share similar friction, if not the arc. They also have something else in common: men, mostly, did the heavy lifting. If in Mughal-e-Azam (1960), Salim mobilised an army to protect Anarkali, the woman he loved, then in the post-liberalised India of Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Raj crossed oceans to woo the unrelenting parents of Simran, the woman he loved. Prem in Maine Pyar Kiya (1989) surrendered a life of plenty to prove his love for Suman, and in Veer-Zaara (2004), a cross-border love story stacked against impossible odds, Veer, an Air Force officer from India, arrived in Pakistan to meet Zara.

Salim and Anarkali in Mughal-E-Azam (1960)

With time, female passivity changed faces without much change in fate. Audacious women were written, but the pluck felt superficial. Geet in Jab We Met (2007) ran away from home, but she still needed Aditya to bring her back; a decade later, Bitti Mishra in Bareilly Ki Barfi smoked with her father, and yet, her fate swung between two men. These are sweeping instances, punctuated, yes, by a few exceptions, but the reading holds water.

The Bengali Woman As An Antithesis

In comparison, someone like Madhu is portrayed as an antithesis. Her autonomy feels as attentive as complete. She has a well-defined job, her family rallies around her, she is vocal about her sexual needs and, more crucially, none of this changes when she falls in love. She takes efforts to meet Shrirenu as much as he does - a detail that speaks volumes about the shared duties they assume. Later, when he shames her, she calls him out.

Rani Chatterjee in Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani (2023) had the same attributes. She fell in love with Rocky, an indulgent man-child in Delhi with a closed world-view. Passion ran high, yet she refused to budge to tradition. In both cases, modernity is not a personality trait but a subtext of their persona. More similarities follow: they pair chiffon saris with sleeveless blouses. Madhu reads Sartre, and, if probed, Rani's favourite author might well be Simone de Beauvoir. Both are culturally inclined and philosophically profound. In private, they possibly worship Tagore and wept the day the Left government lost power in West Bengal. And, in case you did not notice, they are Bengali.

The 'Prototype'

The 'strong-willed Bengali woman' prototype has existed in Hindi films. Madhu and Rani stand on the shoulders of other self-reliant women like Piku (Shoojit Sircar's 2015 Piku) and Vidya Basu (Sujoy Ghosh's 2012 Kahaani). Sure, there are the many renditions of the uncompromising Parvati from Devdas, and Vikramaditya Motwane reimagined O. Henry's The Last Leaf as Lootera (2013) with an unyielding Bengali woman at the centre. But even other films have used this prototype. In Vijay Lalwani's Karthik Calling Karthik (2010), a twisted thriller on an introvert, the free-spirited female character is a Bengali;. Aziz Mirza's Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani (2000) features a ruthless journalist who, of course, is also a Bengali.

Rani's stereotypical Bengali family in Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani (2023)

As real women started staking more claims in public spaces, women in love stories awaited a facelift. Naturally, it made sense for makers (Karan Johar and co) to harness this trope for a wider appeal, to reinvent the Hindi film heroine in romantic films as a Bengali woman in love. Culture comes with the territory, and so does defiance. But Rani and Madhu's representation has been a misrepresentation. If they are to be believed, then a Bengali woman reads Tagore for breakfast, recites Sukumar Ray for lunch, and finishes her day with a Satyajit Ray film. She lives in a giant house, her liberal outlook is without a blindspot, and even though she might have toured across the globe, College Street is her favourite street.

The Allure Of The 'Bhodromahila'

Granted that accusing Hindi filmmakers of exaggeration is akin to complaining about the monsoon in Mumbai. Some things go hand in hand. But the depictions have prompted a wider discourse, because by reiterating a certain kind, propped up by specific caste and class, these films seem to dictate that only the affluent, outspoken, plucky and Liberal Bengali woman (the Bhodromohila to the Bhadralok) is deserving of love. Or, that her story is worth telling. A couple of days back, an account on Instagram thoughtfully questioned the stereotype and asked: "Is every modern Bengali woman really a Rani Chatterjee or a Madhu Bose?" The answer, of course, is no.

But here's the thing: even a forthcoming Rani Chatterjee or a radical Madhu Bose, in the off chance that they exist, were not born as one. Unlike what might be suggested, liberalism is not stuffed in our potatoes, nor is it a virus Bengali women are born with (in a bizarre segue in Aap Jaisa Koi, a hitherto timid woman starts calling out patriarchy after falling in love with a Bengali man, like she has been "infected"). Even the most rebellious of Bengali women have had to earn their rebellion; even the most well-turned-out, sari-clad Bengali woman has had to fight for her sleeveless blouses. One is not born but becomes Rani Chatterjee or Madhu Bose.

Still Raising Boys

In a country like India, where women shrinking themselves to make space for others is the default, such characters are far-fetched on some days and aspirational on others. Perhaps that is the allure. Cinema, after all, is a site of wish fulfilment. But it is also the medium of representation, a space to see and be seen. By assuming that Bengali households are untouched by patriarchy - a belief that collapses when one considers the mounting cases of rape and abuse in West Bengal in this year alone - these films undercut and erase the struggle of Bengali women who stand up for themselves despite, and not because of, their surname. By not showcasing the labour built into it, they squander the chance of celebrating feminism.

Fatima Sana Sheikh as Madhu Bose in Aap Jaisa Koi (2025)

One can argue that such portrayals, however excessive, are designed to subvert the androcentric gaze of love. But women are somehow still getting shortchanged. If, in the past, they were offered ornamental parts in romantic films, then now, they are burdened with the task of teaching men. If, earlier, they waited for grown-up men to show up, then now, they are tasked with rehabilitating boys. Love is no longer the bridge where two people meet but an ideological minefield where one community is pitted against the other. And somehow, despite the cultural agency of female characters, the one gaining from it is - still - not them.

(Ishita Sengupta is an independent film critic and culture writer from India. Her writing is informed by gender and pop culture and has appeared in The Indian Express, Hyperallergic, New Lines Magazine, etc.)

Disclaimer: These are the personal opinions of the author

-

Opinion | Air India Crash: Exactly Whom Are The Two 'Leaks' And The Probe Report Helping?

The speculation, allegations and mythmaking around the AI-171 crash threaten to muddy the truth irreversibly. Who benefits from this mess?

-

Mujib, Tagore, Now Ray: Culture Crackdown In Bangladesh Post Hasina Ouster?

Bangladesh appears to be shedding its past, its cultural history and its shared heritage with India

-

Opinion | The Anguish Of Nimisha Priya And The Imperative Of Compassion

Nimisha's story is, sadly, one that epitomises the hopes and vulnerabilities of many Keralites who seek opportunity in distant lands.

-

Opinion | China, Pakistan, And The Trouble With Keeping Snakes In Your Backyard

While declaring that China opposes all forms of terrorism, its foreign ministry asserts that it seeks to foster amity. Does Beijing really think it can present itself as an honest broker even as it acts like a behind-the-scenes instigator?

-

Amid Row In Bihar, NDTV Explains 'Special Intensive Revision' Of Voter Lists

The voter list revision in Bihar has become controversial with the opposition challenging the exercise and the Election Commission in the Supreme Court.

-

Opinion | The Great Indian IT Crash: Why You, An Engineer, <i>Still</i> Can't Find A Job

In Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune, you will find PG hostels full of jobless coders, waiting, scrolling job portals, wondering what happened to their cherished IT dream. This is a story of a generation staring up a ladder that no longer reaches the sky.

-

Blog | Witch, Warrior, Woman: Radhika Apte Is Done Playing Nice

Apte is a phenomenon - an actor whose range, though often confined to the thematic corridors of thriller and horror, quietly defies the limitations imposed by the very industry that should champion her.

-

Opinion | Gurugram And Its 'Manhattan' Dreams: Fake It Till You Flood It

While news pages are moaning about waterlogged roads in the city, there is a builder boldly advertising, in a newspaper jacket, "luxe suites" in an imaginatively titled "South of Gurugram".

-

Opinion | We Are Indian. Can We Please Say That In Any Language We Like?

Some people still see English as a marker of privilege. Some see it as a barrier. But when you try to shame people for speaking it, you disregard the aspirations of millions who see English as their best chance to create opportunities.

-

Opinion | Can Musk And His America Party Rely On 'Vibes'?

Musk is betting big on a simple truth: that people are tired of politics as usual. He thinks they want disruption, the kind that doesn't just drain the swamp but uploads it to the cloud.